Design is the conscious assembly of concepts, materials, techniques and strategies for a particular purpose. Yet seeing all the exciting possibilities that permaculture offers us, it’s easy to forget this and just end up throwing together a collection of ‘green’ technologies and techniques, only to be disappointed by the result. There’s now no shortage of these ‘green options’ for us to choose from and we’ve been given the impression that as long as we behave in certain ways and buy the right products, we’re doing the best we can.

But permaculture and design is about more than just choosing the right things, it’s also about how we connect them together. Nature abounds with examples of beneficial relationships, showing us the value of this strategy for long-term sustainability. So as permaculture designers, our role is to place components in the best places relative to each other, to create self-sustaining systems that also meet our needs. However, such relationships are often site-related, so we need to be able to consciously design; to become a ‘permaculture chef’, rather than simply learning to follow a recipe. While perfecting this can be a lifelong journey, it’s also not so hard to learn the basics.

While it’s easy to worry these days about our impact on the environment, it’s perfectly natural for us to be shaping it to meet our needs, every species that lives here does just that. The important question that Biomimicry advocate Janine Benyus asks us is whether our choices are well-adapted ones. Permaculture gives us the tools to create systems that support not just ourselves, but future generations too and Life as a whole.

In Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual, Bill Mollison suggests:

These design considerations provide us with clear criteria for how any permaculture design should perform. If we can design systems within these guidelines that meet our human needs, and at the same time support the ecosystem as a whole, then we will be well on our way to a sustainable human society.

We should invest most time and energy in the establishment of a good design, so inputs decrease as time goes on. Conversely, yields may start off small but then increase steadily. At a certain point, the total energy yielded from the site exceeds the total amount invested and the system goes ‘into profit’. One more thing worth remembering is that biologically we’re simply an ecosystem living within a larger ecosystem. And that whatever we do has consequences.

Permaculture advises us that when we design to meet our needs, we should do so in a way that supports the ecosystem as a whole. The permaculture ethics, often abbreviated to Earth Care, People Care, Fair Shares, are our primary guidance in this process. Any ideas that don’t fit with these ethics just aren’t permaculture.

Bill Mollison and David Holmgren also provided us with a set of principles and directives, which have since been adapted and added to by others. The principles of ecology guide us in applying successful natural patterns to design gardens and farms. However, we can be even more creative and apply many of these same principles to people-based designs too. There are also principles that address how we think, helping us to see the gifts in every situation.

You’ll find many more and different versions of these principles on your travels. It’s not so much a matter of which ones are ‘right’, but rather which of them you find useful in your life.

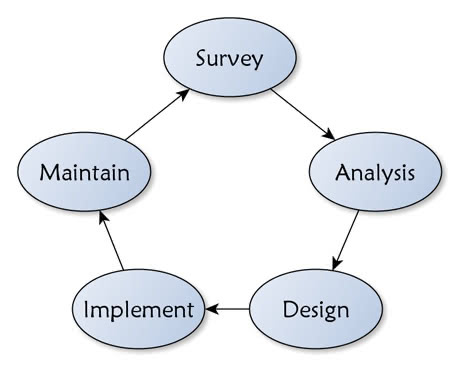

Permaculture has borrowed many useful thinking tools from different places, including several design frameworks from other disciplines. One commonly used is SADI, which comes from Landscape Architecture; the letters standing for Survey, Analysis, Design, Implementation. The value of a framework is that it can guide us through the process of design, reducing the chance that we might overlook something. While each of these stages can be quite detailed in themselves, for us the main things to remember are:

Survey ~ of both the needs of the client(s) and the landscape that will be meeting those needs. This might well include some mapping. The more focus given to this observation stage, the better a design is likely to be. Bill Mollison suggests observing a system for at least one whole cycle, which for a land-based design is a whole year. This shouldn’t prevent us from making changes though, just don’t, as Bill would say, do anything you might find difficult to reverse.

Analysis ~ this is the stage where we take all the information we have gathered and use the ethics, principles and appropriate design tools and methods to help us decide the best elements to choose and how best to connect them together into resilient low input, high output systems.

Design (or as I prefer to call this part Decisions, as the whole process is about design) ~ this is where we commit to our ideas, producing maps and lists that communicate our ideas to our client(s). While attractive maps are helpful at this stage, including your reasons for decisions can help illuminate the design process and increase the likelihood of the clients understanding the bigger picture of how it is intended to function. A design proposal should also include suggested implementation and maintenance plans.

Implement ~ at some point we have to take our ideas and put them into practice. However much time we take to deliberate, we’ll still be surprised by some things that don’t work as planned; so we shouldn’t be afraid to take action. Only by implementing a design do we learn how well it performs in the real world. Mistakes are great opportunities to learn, but good attention to the survey and analysis stages should limit them to smallish ones.

Maintain / Monitor ~ this wasn’t included in the original acronym, but maybe Landscape Architects just implement and walk away. Without knowing how to care for the system (and particularly unfamiliar technologies like composting toilets), it can fail to perform as intended and perhaps be abandoned as ineffective.

Throughout the design process we can make use of many different thinking tools and methods. These can for instance help us to make client interviews fully inclusive, especially when working with larger groups or community designs. They can help us with our decision making processes to ensure we create effective designs and also help us to produce a realistic implementation plan.

Permaculture is neither a specific recipe, nor an end point. Rather it is an ongoing process of harmonious adaptation to nature’s changing conditions. The design process is a gift to us all that can help us to find and stay on our desired path.

Adapted from Permaculture Design – a Step-by-Step Guide to the Process by Aranya

Aranya has been experimenting with permaculture since his design course epiphany in 1996. In the years that followed he designed a collection of gardens, along with a few other non-land based designs, writing them all up to gain his Diploma in Applied Permaculture Design 2003.