The 12 permaculture design principles are thinking tools, that when used together, allow us to creatively re-design our environment and our behaviour in a world of less energy and resources. These principles are seen as universal, although the methods used to express them will vary greatly according to the place and situation. They can be applied to our personal, economic, social and political reorganisation and the ethical foundation of permaculture guides the use of these design tools, ensuring that they are used in appropriate ways.

Each principle can be thought of as a door that opens into a whole system of thinking, providing a different perspective that can be understood at varying levels of depth and application. David Holmgren, the co-originator of permaculture, redefined permaculture principles in his seminal book, Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability. When I started giving talks about permaculture to all sorts of different audiences, I decided to write my own explanations and apply the principle not only to designing gardens and farms but to business, society and culture. Every principle comes with David’s ‘proverb’ and is followed by my explanation.

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

For me this element of stillness and observation forms the key of permaculture design. In a world of instant makeovers, of ‘fast’ everything, having the capacity to observe the seasons, watch the changing microclimates on a patch of land, understand how the patterns of wind, weather and slope affect the frost pockets and plant growth, is an opportunity to begin to learn the deeper aspects of Earth Care. It also makes us more capable of making wise decisions about how we design or eco-renovate our houses and plan our gardens and farms.

“Make hay while the sun shines.”

Intimately connected to observation is the art of capturing energy in a design, so that we minimise the need to seek resources from the outside. In a garden this is about avoiding planting tender seedlings in frost pockets in spring or maximising solar gain by siting a greenhouse/conservatory on the south side of a building so that we can both extend the season and heat a house with passive solar gain. We are attempting to capture water, sunlight, heat, soil, biomass and fertility whenever we can in order to become more self-resilient.

“You can’t work on an empty stomach.”

“The sins of the fathers are visited on the children of the seventh generation.”

When we burn fossil fuels we release CO2 into the atmosphere, trapping heat and increasing temperatures. This causes ice to melt which leads to loss of reflective surfaces, leading to more absorption of sunlight and even higher temperatures. We must accept responsibility for our actions.

“Let nature take its course.”

Whenever possible, permaculture seeks to use resources that can be renewed. This naturally applies to energy but also to ecological building, coppicing, soil conservation, and the planting of perennial food crops, as well as annuals with seed saving. The dangers of relying on non-renewables, technological fixes and speculative money are becoming ever more evident.

“Waste not, want not. A stitch in time saves nine.”

In the UK, we throw away the equivalent of 24 bags of sugar per household per week: 14.1 kg. That’s 29 million tonnes (55% of that is household) per year. I have a favourite saying that the landfill of today will be the ‘mine’ of tomorrow. At PM we have no waste collection and our business is designed on permaculture principles. We reuse first and recycle all possible materials: paper, cardboard, textiles, glass and compost all organic materials, from kitchen waste to shredded paper. The subsequent compost feeds the edible container garden outside our office and provides a medium for growing plants for other projects at the Sustainability Centre.

“Can’t see the wood for the trees.”

When Tim Harland and I designed our house and garden, we read up on permaculture design, forest gardening, renewable energy, eco-architecture and eco-renovation as much as we could. We spent a year observing the land before we started planting and planned how best to make our house a happy, energy efficient place to live in. We observed the seasons, the climatic variations, the weather, the soil patterns, slope and our own human activities on the site as a family.

We also considered the ‘edge’ between house and garden and how we might make this both aesthetic and productive in terms of food crops and energy harvesting. In other words, we started off looking at the bigger picture, the pattern of what sustainable living might be, with examples from other places, and then we refined our exploration into the detail appropriate for our particular site. We didn’t make a ‘shopping list’ of individual items or projects and try to mesh them together in a hotchpotch of what might be regarded as ‘green’.

“Many hands make light work.”

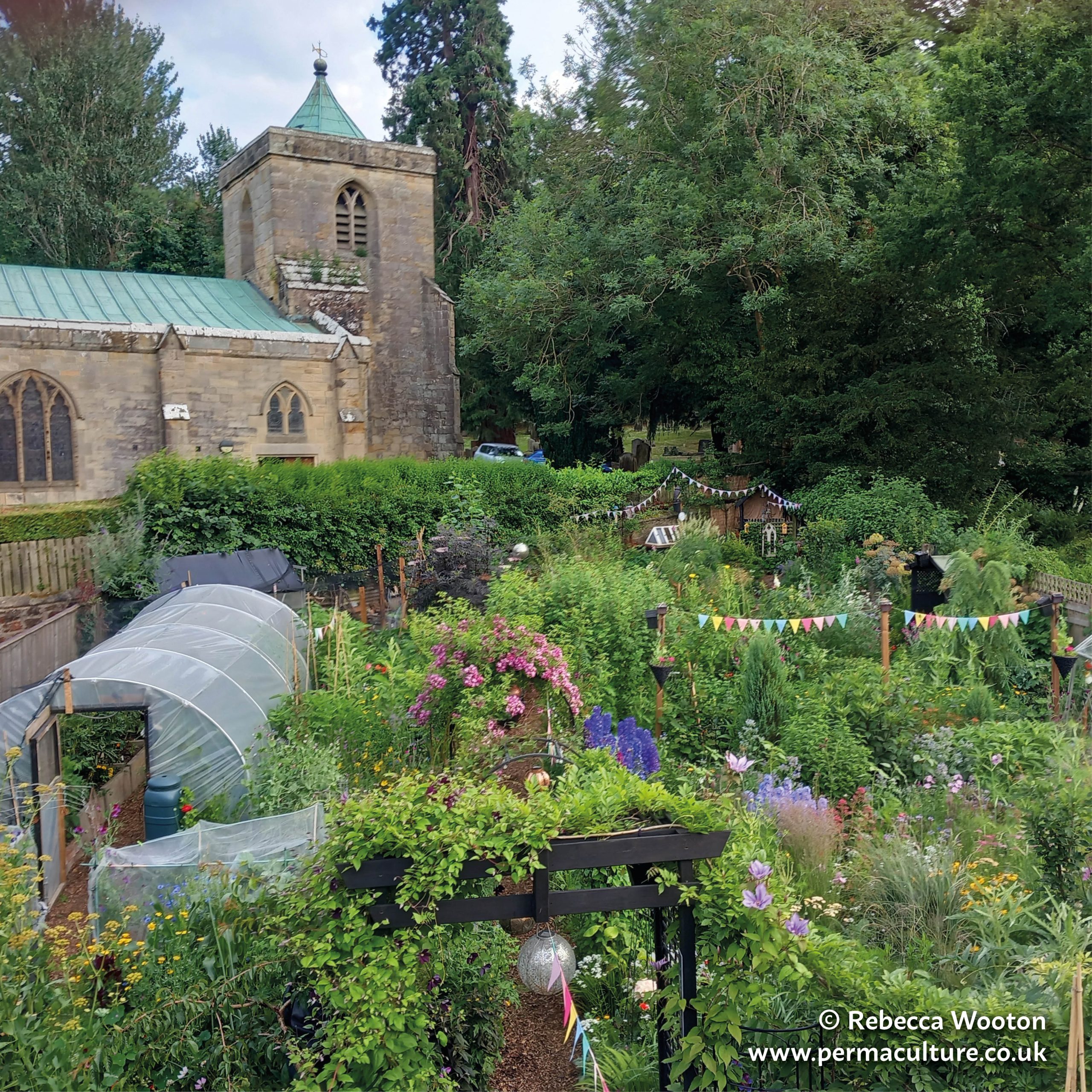

We have a cultural tendency to separate veggie gardens from flower gardens and use hard edges to design our spaces. Companion gardeners will know however that the more integrated the orchard is with the wildflower meadow, or the vegetables are with flowers frequented by beneficial insects, the less pests will prevail. The same is true for people. Cultural diversity yields a robust and fertile culture, whereas a rigid monoculture of politics and religion can bring sterility, even social and political repression.

“The bigger they are, the harder they fall.”

Our society currently depends on vast inputs of fossil fuels, whilst our biosphere is over-loaded by their outputs. The more accessible and fixable our technology and chains of supply are, the more robust the system. This principle speaks of hand tools, of appropriate technology that can easily be fixed, and of relocalisation.

Currently we have a three day ‘just in time’ supply chain of supermarkets. If the fuel supply is interrupted, the super-market shelves will empty at an alarming rate. Better to build resilience into our systems by relocalising our essential needs as much as possible and having technological alternatives that we can fix.

“Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.”

Biodiversity creates healthy ecosystems. Diversity in terms of crops, energy sources, and employment, make for greater sustainability. Valuing diversity amongst people makes for a more peaceful, equitable society. Conflict and wars are the biggest slayers of sustainable development.

“Don’t think you are on the right track just because it is a well-beaten path.”

Examples of ‘edge’ in nature are: where canopy meets clearing in the woodland, inviting in air and sunshine and a profusion of flowers; where sea and river meet land in the fertile interface of estuaries, full of invertebrates, fish and bird life; where the banks of streams meet the water’s edge and fertility is built with deposited mud and sand in flood time, giving life to a riot of plant life; where plains and water meet, flooding and capturing alluvial soils…

Edge in nature is all about increasing diversity by the increase of inter-relationship between the elements: earth, air, fire (sun), and water. This phenomenon increases the opportunity for life in all of its marvellous fertility of forms. In human society, edge is where we have cultural diversity. It is the place where free thinkers and so-called ‘alternative’ people thrive. where new ideas are allowed to develop and ageless wisdom is given its rightful respect. Edge is suppressed in non-democratic states and countries that demand theological allegiance to one religion.

“Vision is not seeing things as they are but as they will be.”

In nature, there is a process of succession. Bare soil is colonised by weeds that are in turn superseded by brambles. Then pioneers follow; like silver birch, alder and gorse which stabilise the soil. The latter two even fix nitrogen to create an environment that can host slow growing temperate climate species like oak, beech and yew. But nature is dynamic and succession can be interrupted by brow-sing animals, storms that fell trees and create clearings or a changing climate that is less hospitable for certain climax giants like oak and beech.

The challenge of a permaculture designer is to understand how all these factors interact with each other in a landscape or on a part-icular plot of land, and design accordingly. It is no good restoring coppice without fencing out deer, or planting trees if they will shade out the solar panel in a decades’ time. Equally well, we need to appreciate how climate change will affect our agriculture, with higher summer temperatures, greater volumes of rain in winter and springtime, and more violent storms with higher wind speeds. Hotter summers may allow more vineyards on the gentle southern slopes of the chalk downland. They may also make English oaks less viable in the south. What then do we plant and how do we design in resilience to our settlements?

One example is to plant more shelterbelts for farmland as well as housing estates and forgo building on floodplains. The principle is deeper than this, however. It invites us to imagine a future world, a world without cheap oil, and a world that necessarily radically reduces its carbon load in the atmosphere. By doing this, we take the first steps towards creating it. We stand on the bedrock of permaculture ethics Earth Care, People Care and Fair Shares, and are empowered by a set of principles that can inform our planning and actions. Human beings can either be the destroyers or the self-elected stewards of our planet. We have the capacity to put our ethics into action, literally to ‘walk our talk’.

With permaculture design, we create the potential for a powerful beneficial relationship with the Earth. We can become stewards for our world whilst still maintaining an openness and humility to accept nature as perhaps our most powerful and wisest of teachers. What a culture we could build if these two perspectives were the bedrock of our civilisation! I believe that as we awaken as human beings and our awareness grows, we turn away from designing our own private Eden and engage more fully with the rest of humanity and the biosphere. We cannot build ecological arks on a failing planet. We are part of an inter-dependent ecological system. There can be no ‘them’ and ‘us’ in ecology. Permaculture is about low carbon, eco-friendly, even abundant living. It is also an ethically based design system for people who want to not only transform their lives and the lives of the people around them, but also to play their part in bringing an ecologically balanced, equitable and kinder world into existence. That is our challenge.

Maddy Harland is the co-founder and editor of Permaculture magazine and author of Fertile Edges – Regenerating the land, culture and hope.