When a complex system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos have the capacity to shift the entire system to a higher order. Ilya Prigogine, Physical Chemist and Nobel Laureate

Welcome back. The late genius Douglas Adams wrote his Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy trilogy in five parts. With this as our beacon of possibility, we bring you the fourth in our three-part series in which we explore the wild promise of our worldwide culture and how we might create a generative, flourishing future we’d be proud to leave behind.

If you haven’t read the previous articles in PM, you’ll find them in PM116-118. I heartily encourage you to find, read and share them; like everything else in PM, these ideas grow best if they’re composted in enthusiastic conversation and the ideas pulled apart and reconfigured by people who think deeply about all we hold to be true and good and beautiful.

For ease, though, we proposed that the death cult of predatory capitalism is drowning in giant slurry pits of its own making and taking the entire eco-sphere with it; that the time has come for everyone to step up, step forward, step together to imagine – and thus usher into being – new systems of governance, value-sharing and community that can shape the conditions for emergence into a new system of being; and that only by creating stories of how a new system could look and work and feel, will we be able to edge our global culture forward to a future where all life thrives.

We borrowed the term ‘Thrutopia’ from Dr Rupert Read of the Climate Majority Project1 to define this new genre of writing/creating that envisions a flourishing future predicated not on scarcity, separation and powerlessness, but on sufficiency, agency and connection.

Finally, we encouraged anyone and everyone to begin to explore the possibilities of a life differently lived: to talk about it, write about it, sing about it, make videos about it… everything.

Change in complex systems

So that’s where we’ve been. Along the way, we glossed over a number of ideas, notably the theory of change in complex adaptive systems: there is more to explore here and this moment feels timely. Not just because some of these ideas need to set deeper roots in our imaginations, but also because the world is changing faster than we might imagine, possibly faster than we can imagine, and there are some concepts now which we need urgently to consider that were more peripheral when I first started writing these articles in February of last year.

Here and now, let’s stare a little harder at the nature of systems, tipping points and the theories of change that are centred around them. Many of our core concepts were proposed by the Nobel laureate Ilya Prigogine.2 He was a nuclear chemist, and it may be that concepts which apply at the atomic level don’t translate perfectly to the level of hyper-complex human cultures in a world of global real-time communication, but they do offer a model that we can grasp and I have yet to come across anything better.

Prigogine established that ‘when a complex system is far from equilibrium it reaches a bifurcation point where further instability leads the system either to collapse into chaos and extinction or to emerge into a new system.’3

Emergence

This is where our theories of emergence from complex systems arise from, and these, in turn, are the foundations on which we build hope: not the pre-Tragic4 hope of the techno-optimists and eco-modern dystopians who see technology as paving the way to a future in which the web of life is an ‘aesthetic option’ (which can, by definition, be rejected and then destroyed), but a post-Tragic hope that sees the reality of our Meta-crisis5 in all its raw chaos, but holds to the possibility of emergence as something worth striving for.

If we’re going to pin our hope on this, then we need to understand a little more of what emergence looks and feels like. Happily, our world offers endless examples of complex systems that emerge into new systems under specific circumstance.

Most commonly referenced is the caterpillar, which, at a given point spins a cocoon and dissolves into the chaotic DNA soup of a pupa. Pretty soon, imaginal cells arise amidst the chaos. In the beginning, these are assaulted as being ‘other’ and removed by the system, but more emerge and begin to coalesce into imaginal islands which cohere to form imaginal organs which eventually become the butterfly or moth that (in a rather neat personification of our metaphor) emerges from the cocoon.

The leads us to Prigogine’s second most quoted aphorism, which states that ‘Small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos have the capacity to lead the entire system to a higher order’.6

This is acquiring the weight of prophecy in certain circles now and those of us who bandy it around tend fondly to believe that we’re in the process of creating small islands of coherence focused on whatever we hold most dear at the time. We may even be right.

It’s a comforting thought, but one we can’t really test, because one of the over-riding axioms of systems thinking is that no system is predictable from the standpoint of the one that preceded it.

If ten thousand ants mill around on the edge of a chasm that none can cross alone, the exact nature of the bridge they will form with their bodies is wholly unpredictable. The fact that they can, and probably will, form such a bridge, though, is as predictable as is the emergence of the red admiral from the cocoon: it’s the caterpillar or the single ant that can’t predict the outcome. Those of us standing outside can make an educated guess based on previous experience.

Living, breathing adaptive miracles

So let’s park this and consider the current moment in the history of humanity. Each of us – you, me and anyone we meet – is the endpoint of billions of years of evolution. Our distant predecessors were hydrogen molecules and, when those hydrogen molecules gave rise to more complex atoms and then compounds and finally to life forms that could reproduce; we are the descendants of those that lived long enough to do so.

The odds against us being here are staggeringly high. We are living, breathing miracles. We are also living, breathing complex adaptive systems formed of cells that are themselves complex adaptive systems, bunched together into organs that are complex adaptive systems, to make human beings who are complex adaptive systems who then join together in communities of place, purpose or passion to form hyper-complex adaptive systems that span the globe and communicate across space in real-time.

In a healthy society our networks of place, purpose and passion would be generative spaces where we were encouraged to bring the best of ourselves to a shared endeavour whose focus emerged from the totality of the system. There are places in the world where this is happening.7 By and large, though, in our crumbling end-stage somewhat toxic mess of a culture, our communities tend instead to become echo-chambers of self-delusion.

Linearity

Inherent to these echo-chambers is a clinging to linear thought. We are the inheritors of what was laughably called The Enlightenment, which projected the emotional illiteracy of public schoolboys who grew in an atmosphere of punishment, privation and (at least financial) privilege onto an outer world that was wildly scary and existed to be tamed.

Imposing linear narratives of cause and effect gave the illusion of control which allowed this astonishingly toxic culture to spread narratives of progress over processes of colonisation, corruption, inequity and wanton destruction while ignoring the wider systemic impacts until way, way too late.

If you’re reading this magazine, you know this. You know, too, that linearity is not the way the world works: the Law of Unintended Consequences applies to pretty much everything we do (I’m using ‘we’ here to denote the hegemonic narratives of the death cult, not necessarily you and me) and the ripple effects are vast, unmeasured and very likely unmeasurable.

If we pull a couple of areas at random out of the hat of unknowing, then farming and health are exuberant examples of policy areas where linearity has been practiced to catastrophic effect.

Mid-way through the last century, we were pretty good at measuring nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium (NPK) and acidity (pH) levels in soil, and had ‘demonstrated’ to ourselves in carefully controlled trials that ignored the astonishing complexity of the soil food web that these and only these were essential to the growing of healthy plants.

We turned the creation and application of these macro-nutrients into a global industry that proceeded to destroy living soils worldwide, breaking through planetary nitrogen and phosphorus boundaries with terrifying speed8 while wreaking havoc with freshwater and marine ecosystems and, at the same time, creating food that was and remains deficient in micronutrients and phytochemicals and almost certainly a host of other things we can’t measure yet. We are now at the point where Dr Robert Lustig asserts that 93% of US citizens have metabolic disease signified by dysfunctional mitochondria.9

We are just beginning to understand the complex links between the soil biome and the human (and animal) gut microbiomes, but already we can safely predict that processed foods do not contain the complexity we evolved to need and that the eco-modernist concept of ‘Precision Fermentation’ is attractive only to the small sub-group of technophiles for whom the term was focus-group tested. The rest of us want (need) real, whole food grown in living soil as close to our location as possible.10 Yay for Permaculture.

So let’s throw out another aphorism: No problem is solved from the mindset that created it.

Applying this to the theories of change in complex systems tells us that our linear cause-and-effect mindset is not ever going to be able to map a way through, that we won’t solve the meta-crisis with regenerative farming, or permaculture, by all turning vegan, ending the use of fossil fuels, regulating Forever Chemicals or [fill in your favourite fix]. There is no possibility that any single thing or even suite of things will fix this: the Meta-Crisis is bigger than all of us.

So what can we do?

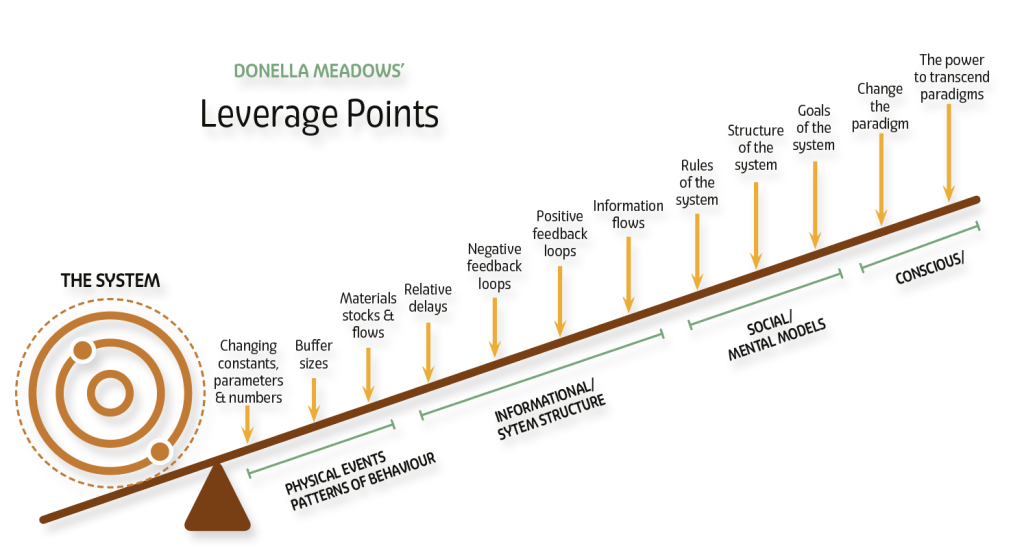

Back in 1999, Donella Meadows, one of the greatest minds in the systems thinking world, created a list of 12 leverage points that could affect change in any given complex system.11

Meadows stacked her leverage points in order of efficacy with ‘Changing constants, parameters and numbers’ lowest on the list: essentially tweaking regulation, laws and tax points. She proposed this in the last year of the old millennium and one of the many distressing features of late stage capitalism is that, two decades on, the system still elevates to power people who believe that tweaking constants and numbers is a useful thing to do. Granted, the system is designed to amplify the clout of people who will fight tooth and brain-dead nail to maintain the status quo, but even so, it’s hellish depressing.

Letting go

So let’s be clear: regulation is fine, but it’s not enough. Yes, we could regulate industry from the fossil fuel companies downwards. (We could try. I suspect we might hit up against some hard edges if we did, but it’s a nice theory.) Yes, we could mandate massed insulation of our homes/offices and give everyone a free air-source heat pump. We’d have to redefine our relationship with money first, but that’s pretty much a given anyway. Yes, we could create universal basic services and mandate a Platonic maximum: minimum wage ratio of 20:1. All of these would be good. None of them, not even all of them combined, would be enough – unless they were coupled with Meadows’ top leverage point: Transcend All Paradigms. I learned of this at Schumacher College in the Masters in Regenerative Economics course. Or rather, I was taught the 12 leverage points and promptly forgot the top one. I spent four years in a state where it seemed not to exist and threw all of my energy at the penultimate one, ‘Change the paradigm’. That seemed do-able. I could imagine how it might happen. But ‘Transcend All Paradigms?’ That means letting go of even the idea that we have to let go of everything. How in the name of all that’s good and right and beautiful are we supposed to do that?

I’m edging towards ideas now – and so the fifth in our now-ongoing series examines what this might mean, and how we might go about it to create the flourishing future we’d all be proud to leave behind.

Dream well in the meantime.

This article originally appeared in Permaculture magazine issue 119