Hazel is a multi-purpose champion of a plant that is super easy to grow, produces delicious nuts, pliable wood that can be crafted into a variety of products, provides early fodder for bees and an encouraging spectacle when flowering during the mid winter.

What more can I say… a plant so good people started naming their daughters after it.

When we speak of hazel, we are generally referring to two species, Corylus avellana and Corylus maxima. The two species produce slightly different shaped nuts and take different growth forms. Corylus avellana produce hazelnuts and Corylus maxima produce filberts. There are 14-18 species in the Corylus genus but many of the European cultivars we have nowadays are Corylus avellana, Corylus maxima or the result of hybrids between these two species. This post we will focus solely on these popular nut producing species.

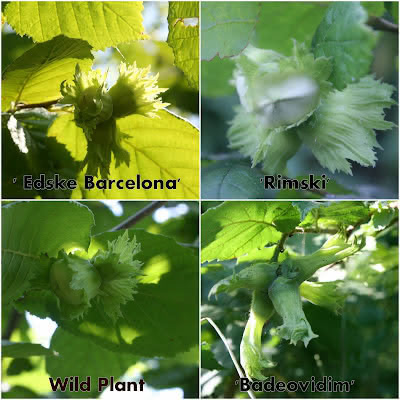

The leafy bracts that envelope the nuts are the easiest way of telling them apart

During this post we’ll take a close look at these versatile plants, including how and where to grow them, growing them in polycultures, how they can be used in agroforestry systems, coppicing hazel, and we’ll look at some of my favourite hardy productive and disease resistant cultivars that we are offering from our Bionursery.

Latin name – Corylus avellana, Corylus maxima

Common name – Hazel, Hazelnut, Cobnut, Filbert, Spanish Nut, Pontic Nut, Lombardy Nut

Family – Betulaceae

History – Pollen counts reveal that Corylus avellana was the first of the temperate deciduous forest trees to immigrate, establish itself and then become abundant in the post glacial period. Humans have been enjoying hazels since prehistoric times and it is thought by some that hazelnuts provided a staple source of food before the days of wheat. Evidence of large-scale Mesolithic nut processing, some 9,000 years old, was found in Scotland and hazels have been used extensively across the temperate zone throughout all civilizations.

Corylus avellana – common hazel

Description – Corylus avellana – Grows as a small tree or large shrub commonly reaching heights of 5m with a 5m spread, but sometimes can reach twice that height and takes a tree like form. The leaves, that open in late April and May and fall in November, are almost circular with double toothed edges and a short pointed tip. The leafy bracts are shorter than the nut.

Description – Corylus maxima – Grows as a large shrub 6m high with a 5m spread. Resembling C. avellana but with young grey twigs, glandular and bristly leaves that are wider, longer catkins and leafy bracts that are tubular and closed, twice the length of the nut. The nuts are also longer than C. avellana. Both species are monoecious. The male flowers are encased in catkins that brighten up the landscape in the winter. The female flowers are tiny red tassels that emerge from buds on the stems.

Sexual reproduction – As mentioned above, the plants are monoecious, producing male and female flowers on the same plant. The male flowers are held in catkins that form during the previous summer and open in the dead of winter and flower through to early spring. There are around 240 male flowers in each catkin and these produce the pollen. Give the catkins a flick in late February to see a small cloud of pollen erupt. Contrary to the wonderful spectacle of the male flowers, female flowers are almost invisible unless you are actively looking for them. They are tiny individual flowers, visible only as red styles protruding from a green bud-like structure on the same branches as the male flowers.

A wind pollinated plant, the pollen from the catkins blows to reach the female flowers. If successfully pollinated and fertilised the female flower will grow to become 1-4 nuts for C. avellana or 1-6 nuts for C. maxima.

Growing range – Corylus avellana is native to western Asia, north Africa and most of Europe, from British Isles eastwards to Russia and the Caucasus, and from central Scandinavia southwards to Turkey. Corylus avellana is native to the Balkans and Asia Minor but is widely naturalised elsewhere.

Both species are pioneer plants found in a range of habitats. As a component of ancient forests they prefer moist lowland soil and are often found growing in the shade of deciduous trees, especially oak. They can be found in hedges, meadows and pastures, on the banks of streams, waste places, abandoned plantings, the edges of woods, on steep slopes and by paths and roadsides. Hazel grows naturally up to altitudes of 700m.

Hazelnut-producing regions of the world are all close to large bodies of water, which moderate the climate. About 70% of the world’s hazelnut production comes from the black sea region of northern Turkey. Italy produces about 20% of world production. Spain, France, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the United States produce most of the rest.

Hardiness USDA

Corylus avellana – Zone 4-8

Corylus maxima – Zone 5-8

Ecology – Hazel flowers are an important source of pollen for bees and other pollinators. The pollen-bearing catkins can be available to pollinators from as early as late January – late March. Hazel leaves are used as food plants by the larvae of various species of Lepidoptera. The nuts are used by dormice to fatten up for hibernation and in spring the leaves are a good source of food for caterpillars, which dormice also eat. Hazelnuts are also eaten by woodpeckers, nuthatches, tits, wood pigeons, jays and a number of small mammals.

Climatic limitations – Both species crop best in areas with cool, moist summers and mild cool winters or in maritime climates. Areas with high summer temperatures are not ideal although good cultivar selection can improve results. Areas with extreme winter cold can also be problematic. The shoots of the plants are hardy to -29oC (-20oF) although winter temperatures below -10oC (-13oF) during the flowering period may damage the male flowers reducing the likelihood of fruit set that year. The plants will not grow well in tropical or sub tropical climates and require a winter chilling period of 800-1200 hrs below 7oC (45oF) which is similar to apples.

Soil – Hazel tolerates a wide variety of soils from calcareous to acid, loam to clay and prefers soil that’s well drained and fairly low in nutrients; overly rich soil gives plenty of leaf growth at the expense of flowers and nuts. Hazels will not grow well in water logged and peaty soils. Shallow soils will restrict the growth and height of hazel.

Location – If growing for nut production in cold climates you should avoid planting in frost pockets, and in hot climates avoid windy sites. Hazelnut trees also cannot tolerate excessive heat or a long dry season. A sheltered area with a reliable source of irrigation is essential in hot climates.

Pollination – Hazels are wind pollinated. As mentioned above, cold weather (-10oC and under) during the flowering time can destroy flowers and reduce fruit set. Heavy rain during the time where pollen is being released can also suppress the amount of pollen carried in the air and moist conditions destroys pollen viability.

The plants are in theory self fertile meaning the pollen from the male flowers can pollinate and fertilise the female flowers on the same plant. However, the blossoming times of the male and female flowers on the same plant do not always coincide and for this reason it is recommended to plant two or more different cultivars to increase the likelihood of pollination occurring. Wild growing hazel nearby will serve as good pollinating agents for most cultivars and there are many cultivars that work well together to ensure fuller cropping. There are some cultivars that absolutely require pollinating partners so research your cultivars well A good rule of thumb for how many pollinator plants you need to support you main cropping cultivar is 1-18. On sites where wet weather is common during the flowering period this can be increased. The pollinating partner should be a maximum of 45m away and upwind from the main cropping plants.

Pollen is released from the male flowers in bursts across a 4-6 week period in January – March. Interestingly, the pollen germinates as soon as it reaches a receptive flower but the fertilisation process does not take place for another 4-5 months in June. Once fertilised the female flowers develop into nuts very rapidly with 90% growth occurring within 4-6 weeks.

Fertility – On good soils hazel will not need fertilisers. On poor soils, planting out with 30 L of compost (applied to the surface) and mulching well with straw and repeating this each spring for 4-5 years will provide a good boost to growth. Planting nitrogen fixing companions can also be very effective.

Irrigation – In cooler climates such as the UK, irrigation is not necessary. In warmer climes with hot summers and long periods without rain, applying 30 L of water per tree every 3-4 weeks without rain and mulching well is very effective.

Weeding – Mulching plants with a 10-20cm deep mulch each spring and pulling weeds that start to grow through in the summer is good practice, especially when the plants are young.

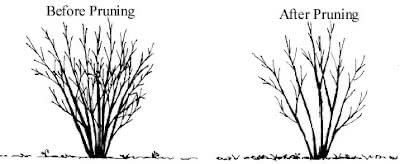

Pruning – When planting out single stemmed whips, it’s good practice to prune the top down to 45cm to encourage lower branching (a practice known as formative pruning). Hazel plants often sucker (send up many shoots from the base of the plant). Suckering growth should be removed to keep the stems clear and the crown less congested. Beyond formative pruning and removing suckers we don’t prune our hazels but there is a tradition, as with most fruit trees, to prune in order to achieve an open centered goblet shaped bush.

If you are going to prune than it’s important to know that female flowers (that will form the nuts) are produced from buds on growth from the previous seasons growth. For optimal nut production you should aim to have plenty of previous years stems, at least 15-25cm long.

I read an interesting comment regarding a traditional pruning method used to increase nut production called ‘brutting’. This involves prompting more of the trees’ energy to go into flower bud production, by snapping, but not breaking off, the tips of the new year shoots’ six or seven leaf groups from the join with the trunk or branch, at the end of the growing season. I’ll be trying this on a few of our plants this year.

Harvesting – The nuts are fully ripe when the husks begin to yellow and can be picked by hand. Nuts will naturally drop over a 4-6 week period. It’s important to not pick before they are ripe as they will shrivel and do not keep well.

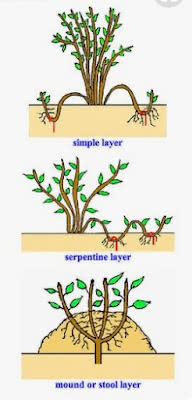

Layering and stooling

Propagation – We have grown hundreds of hazels from locally gathered seed and this is a very easy and reliable method to propagate these plants. Most of our seedling stock we use for coppice plants and hedging plants. For nut production we use cultivars as they generally fruit within the third and fourth year after planting and you know what kind of nut you will end up with.

Seedlings can take up to six or seven years to produce nuts and you never know what they will be like. Saying that, we have some great nut producing seedlings that we propagated from local plants. They appear to be more resistant to the winter cold and have been providing a reliable crop each year even after bitter cold late winters.

Another great way to propagate hazel, including cultivars that are grown on their own roots, is by stooling and layering. Stooling involves heaping soil at the base of the plant, leaving it for 12 months and then dividing the rooted stems. Layering is burying the stems in the soil for 12 months and cutting them off the main plant once the stem has rooted. Hazels that are grafted onto their own roots will send up suckers. The suckers can be dug out in the winter and planted on. The suckers can be a nuisance and will need cutting back to promote better production. Corylus colurna – Turkish hazel is often used as a rootstock as these are non-suckering and have a deeper rooting habit. Cultivars on Corylus colurna rootstocks are often very vigorous.

Excessive heat – Hazelnut trees cannot tolerate excessive heat or a long dry season. They are especially sensitive to drying in windy conditions.

Cold injury – Although a very hardy plant, when growing for nut production the trees are vulnerable during the flowering period in early – late winter. Temperatures below -10oC (-13oF) during the flowering period will damage the male flowers and destroy the pollen reducing the likelihood of fruit set that year. Because not all catkins elongate at the same time, crop damage usually is minimal if there is only a brief cold spell.

Insect/pest – Grey squirrels are major pest of hazels. Nut weevils – Balaninus nucum can destroy the maturing nuts. Beetles lay eggs in the immature nuts. The eggs hatch into maggots that eat the maturing nut and bore out of the shell to pupate in the soil where they overwinter before hatching, mating and laying more eggs in the next crop. Clearing up the fallen nuts is good way to control this pest. Running chicken under the hazels in September can also disturb the pupae in the soil.

Nut Weevils – Balaninus nucum Photo from www.flickr.com/photos/eric-dutoit/5956692789

Disease – In the US this species is affected by Eastern Filbert Blight (EFB), which is caused by the fungus Anisogramma anomola and is fatal to trees. However EFB can be controlled by a variety of management strategies and does not present a major threat to the species as a whole.

Bacterial blight – Xanthomonas campestris pv. corylina causes leaf spotting, dieback of branches and in worst cases death. Trees under stress are most susceptible.

Suckering – Hazels can sucker profusely and the suckers need to be cut back to allow an open crown and avoid congestion. There are cultivars that do not sucker, generally those grown on the Corylus colurna root stocks.

Allergies – The pollen of hazel species are often the cause for allergies in late winter or early spring.

Beyond the nutritious delicious nuts, hazels can be used for a variety of purposes.

Wood – Hazel is almost as well known for coppicing as it is for its nuts. The poles from coppice (known as ‘wands’) are long and flexible and have traditionally been used for wattle fencing, thatching spars, walking sticks, fishing rods, basketry, pea and bean sticks and firewood. The wood is soft and easy to split but not very durable (see ‘hazel coppice’ below).

Oil – The nut oil is used as edible oil and contains 65% of a non-drying oil that can be used in paints, cosmetics etc.

Animal fodder – The twigs can be used to feed rabbits and goats all year around and the leaves are very palatable to cattle.

Leaves – Leaves contain on average 2.2% nitrogen, 0.7% phosphorous and 0.12% potassium and when applied as mulch make a great fertilizer. The plant has potential to be grown as chop and drop component in a polyculture system.

Hedging – Hazel makes a great hedge taking well to trimming and providing a dense screen. Nut production is not as high as when grown as free standing plants but some nuts can be harvested from the hedge. The plants are also tolerant of wind and a two or three row windbreak can be set up where alternate rows are coppiced on a seven year cycle.

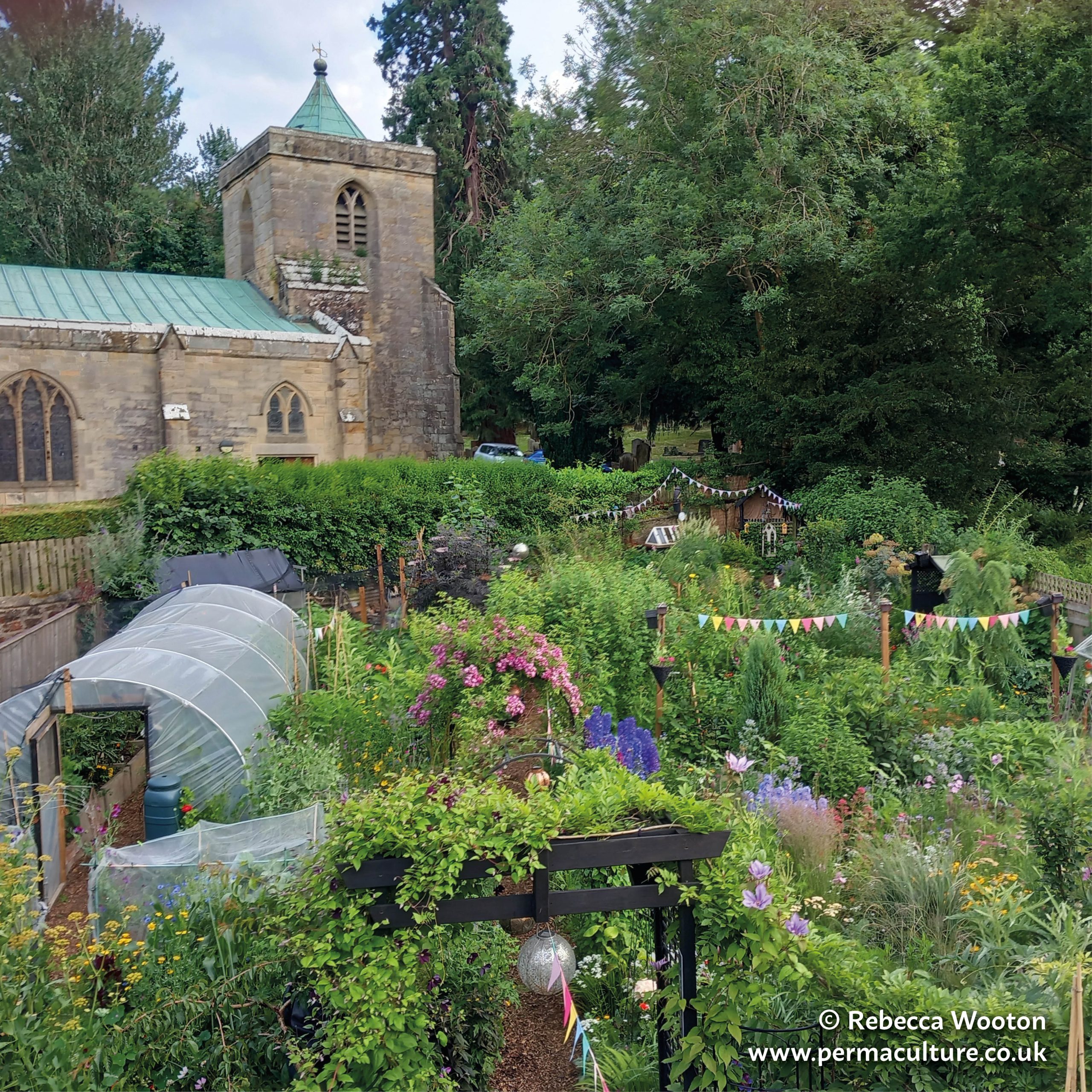

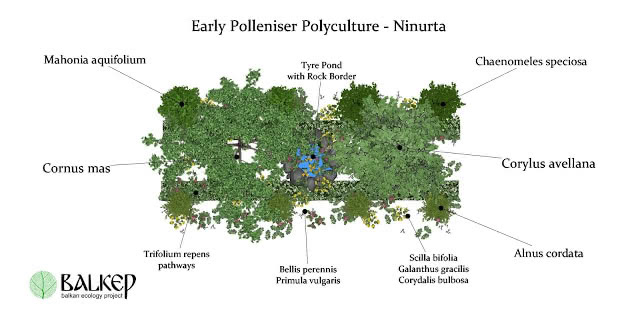

Bee fodder – Hazel is an excellent source of early forage for bees providing a source of pollen from February through to March. We include hazel in our Early Polleniser Polyculture, a polyculture dedicated to providing an early source of pollen/nectar to a wide diversity of pollinating insects.

The Early Polleniser Polyculture

Medicinal uses – The leaves are used in allopathy: their effect is to stimulate circulation and bile production, and they are used for liver and gall disorders. Hazelnuts are rich in protein, monounsaturated fat, vitamin E, manganese, and numerous other essential nutrients.

Other uses – The finely ground seeds are used as an ingredient of face masks in cosmetics.

Hazelnut trees can produce a few nuts when they are two or three years old, but they are not considered commercially productive until four years of age and reach peak production from years 10-15. Mature orchards can produce 1-3 metric tons per ha. An orchard can remain productive for about 40-50 years if managed well and kept free of disease.

| Yield per mature tree | Yield per acre 4050 m2 | Yield per Ha 10000 m2 | |

| Average production | 3-5kg | 880-1760lbs | 1-2 tonnes |

| Max production | 11kg | 2640lbs | 3 tonnes |

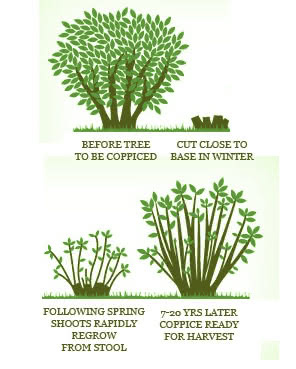

Example of coppice: www.greenwaytreecare.co.uk/images/Coppicing2.jpg

Hazel coppice has been practiced extensively in the past and still provides an excellent source of valuable wood especially if you are adding value with wood crafting.

Contrary to what you may expect, coppicing the hazel can extend the life of the plant considerably with some well managed coppices being centuries old.

Hazel can be grown on various coppice cycles for a supply of poles (‘wands’) that are used for a variety of purposes as listed above. A 7-10 year rotation is often practiced and is planted out at a rate of 1500-2000 plants per ha (spacing is 2.2-2.6m between plants).

In the 7th – 10th year the shoots should be 4-5m long and can be cut at any point during the year apart from August but is usually carried out in the winter. If you cut the coppice in the summer, leaves from the wood make an excellent cattle feed or mulch. Regrowth will quickly reestablish and is vulnerable to browsing from wild and domestic animals. After the first few coppice cycles, regrowth will be fast but after 15 years it will decline. If a hazel coppice is not well managed i.e. cut at regular intervals for 40+ years it will die back.

How much wood can be harvested? A site with 1500 plants per ha can yield 20 tonnes of dry wood or 40m3 of wood per ha per cycle.

Hazel coppices are often combined with standard trees to make a two storey forest. Sweet chestnut is a classic combination in the South of England. Oak is also very commonly grown with hazel at a rate of 30-100 standard trees per Ha. Too many standard trees will shade out the hazel.

Hazel (in the middle) with standard sweet chestnut trees in the background

Hazels are excellent plants for use in polycultures. They are tolerant of shade so suitable in the under storey, are not very nutrient demanding or competitive and are relatively compact and easy to manage. They tolerate pruning very well and can be used for chop and drop plants grown between fruit trees or in hedgerows. If nut production is sought after they should be given a prime position but can still accommodate a range of productive and useful plants around them.

We have used hazel in various polycultures including living hedges, main crop contour plantings and habitat polycultures.

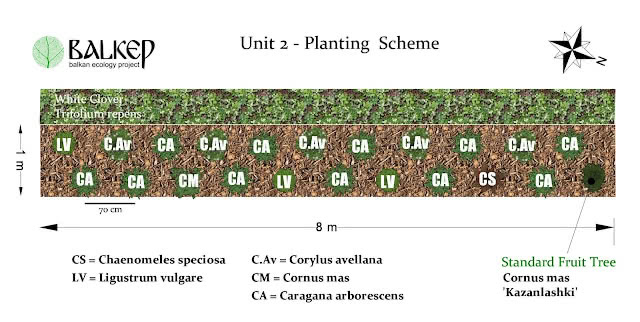

Here’s an example of a design with hazel planted in a polyculture hedge.

I included hazel in a mixed species living hedge I designed for Permaculture Orchard – Orehite Ranch – Veslec

Here’s a short list of ground cover and bulbous plants that we observe growing well with hazel.

Bellis perennis – Daisy

Primula vulgaris – Primrose

Scilla bifolia – Alpine Squill

Trifolium repens – White Clover

Corydalis bulbosa – Spring

Fumewort Galanthus gracilis – Snowdrop

There is great potential for hazels in agroforestry systems. Traditionally in Europe, hazels were grown in a silvopasture system with sheep grazing the pasture beneath the trees, which has an added benefit of controlling suckering growth. Hazel has also been grown with vines and in Kentish orchards gooseberries and currants were traditionally inter planted with young hazel.

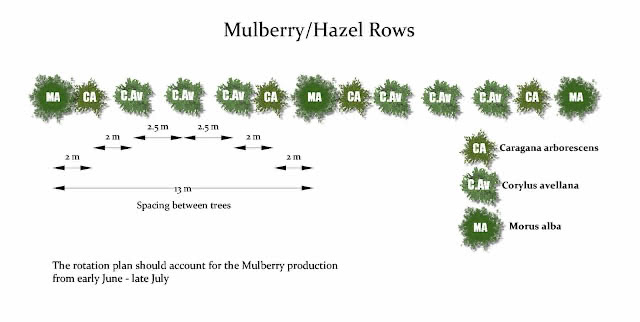

I’ve included hazel in a few agroforestry designs the most recent being a 30 ha pastured poultry system where we’re using hazel amongst mulberry planted on contour.

Being shade tolerant the trees are good candidates for use in an under storey. In deep shade the plants will not produce a significant yield of nuts but they can be used for coppicing or mulch production. In partial shade they can still produce good yields.

There are hundreds of hazel cultivars throughout the world, not to mention the hybrids, American and Chinese species or the Trazels, Filazels and Hazelberts (perhaps a topic for another post).

Most cultivars belong to Corylus maxima but there are many Corylus avellana and many grafted onto Corylus colurna rootstock. When selecting cultivars for your garden there a few things to consider.

Below you can find profiles of some excellent cultivars that we have on offer at our Bionursery.

Corylus avellana – ‘Ata Baba‘

Corylus avellana – ‘Ran Trapezundski‘

Corylus avellana – ‘Rimski‘

Corylus avellana – ‘Tonda Gentile‘

Corylus avellana – ‘Cosford‘

This post originally appeared here: https://balkanecologyproject.blogspot.co.uk/2017/07/the-amazing-hazel-essential-guide-to.html

Paul runs the Balkan Ecology Project in Bulgaria with his wife Sophie Roberts and their two boys Dylan and Archie.