When I first started planning the infrastructure here at Quinta do Vale, I was adamant on including a worm composting toilet – I intended to use Joe Jenkins‘ dry ‘humanure’ composting toilet system throughout. It’s simple, easy to construct and maintain, portable even, and doesn’t require separation of urine from faeces. And it’s an efficient thermophilic composting process with a well-balanced output. It’s no wonder Jenkins’ toilets have been dubbed ‘Loveable Loos’. What’s not to like?

Many people though dislike dry toilets. If there’s to be a mass movement towards better ways to deal with our sewerage, then this can’t be ignored – and here’s where the vermicomposting flush toilet comes in.

Quinta do Vale is an off-grid permaculture project of 2.5 hectares in the mountains of Central Portugal. It’s an evolving demonstration site for many aspects of sustainable living, with a particular emphasis on off-grid infrastructure. It’s run by myself, Wendy Howard.

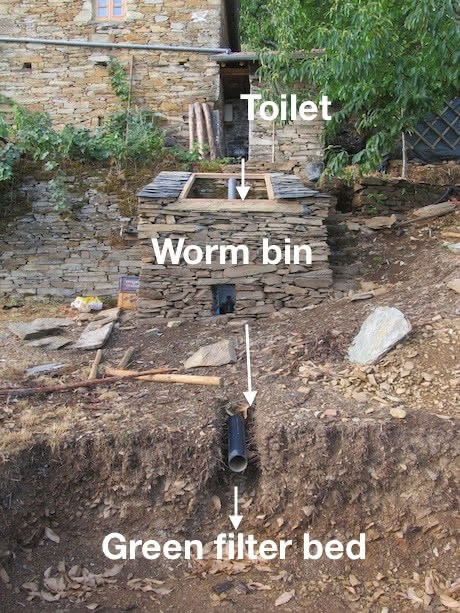

In 2013, we were converting an old hen coop into an outhouse toilet. Coincidently, at the same time I came across Anna Edey’s experiments with vermicomposting flush toilets in Massachusetts, USA, two decades ago. It’s described on the website promoting her book. Edey’s website didn’t give full details, but there was enough information for me to work the rest out for myself. As it happened, the situation of the outhouse was ideal for installing a similar system, so that’s what I did.

From a conventional flush toilet, flushings drain through a waste pipe into an insulated plastic container. The container holds a large quantity of worms who inhabit the surface layers of a mass of carbon-rich organic material (wood shavings, bracken, leaf litter, etc. topped with a starter layer of half-processed compost).

When the flushings enter the container, the solids remain on the surface to be processed by the worms and the liquids drain through the organic filter material and exit the container. They then pass through another waste pipe to a growing bed, also full of carbon-rich material, where they’re taken up by plants or processed by soil bacteria.

For my vermicomposting flush toilet, I used a second-hand 1,000-litre plastic IBC to form the basis of the system. We made an access hatch by cutting half of the tank’s top out. It slots back into place neatly, held by the screw-top lid to the central opening (through which the waste pipe empties into the tank) and an aluminium bar which clips onto the frame each side. Once the tank was sited, we connected 110mm plastic waste pipe to the outlet and dug it into a trench leading to the growing bed.

The tank is sited immediately below the toilet in a dry-stone schist enclosure. As the walls were built, insulation was added to keep the worms within their optimum temperature range of 13-27°C, winter and summer. Closest to the tank, we used sheets of polystyrene insulation, and filled the gap between the insulation and the stone wall with Leca (lightweight expanded clay aggregate). A relatively lightweight galvanised corrugated metal hinged roof makes access to the tank simple. More polystyrene insulation was fixed to the underside of the roof and the top of the tank.

The growing bed, about 1.5m³ in volume, contains 0.5m depth of wood shavings, leaves, etc. to act as an organic sponge and carbon reserve. The black water is piped into the bed and flows through a branched system of perforated 40mm waste pipes laid in the upper layers of organic material. This one bed should be sufficient to deal with the comparatively small volume of liquid likely to be generated by the toilet (greywater goes elsewhere). The bed is unlined – there’s no possibility of contamination of groundwater or neighbouring properties and if there’s any seepage through the filter after large amounts of rain, it will simply contribute fertility to the fruit trees on the terrace below.

Once the water supply was connected to allow for flushing, the system was ready to go. The original plan was to start things off with worm-rich horse manure, perfect for a wormcomposting system, but a cold wet February was the wrong time to find worms in the manure heaps. Instead I obtained a kilo of worms – about 5,000 Eisenia fetida or tigerworms – from eBay and added them to the tank along with some recent additions to the humanure compost heap and some kitchen scraps. We then started using the toilet. The green filter bed was backfilled with topsoil and planted with a lemon tree. More nitrogen-loving plants will follow.

During the initial settling-in period, there was a slight smell from the container, but it disappeared within a week and the system is now working well.

See more at www.permaculturinginportugal.net and www.facebook.com/QtadoVale

More on composting toilets, see Maddy Harland’s ‘Poo Palace’ in PM117 HERE. All back issues are available to read for free when you subscribe. More details HERE.