Growing my own mulch has long been a goal of mine. We use a lot of mulch in the nursery and garden and at the moment I have no problem sourcing straw but if/when the day comes that the farmers start using their own straw to improve their soil (which is becoming a more common practice), I’ll be needing to step up my mulch growing efforts. Currently, I grow enough mulch to sustain my perennial beds and around 10% of my annual beds but rely on imported straw for mulching the other 90% of annual vegetable and nursery beds.

My ideal mulch plant grows fast, is drought tolerant, competes minimally with crop plants, does not contain seed that easily spreads, is easy to handle and cut, i.e. not thorny/prickly or tough and fibrous, and can biodegrade relatively quickly (thereby returning the nutrients back to soil).

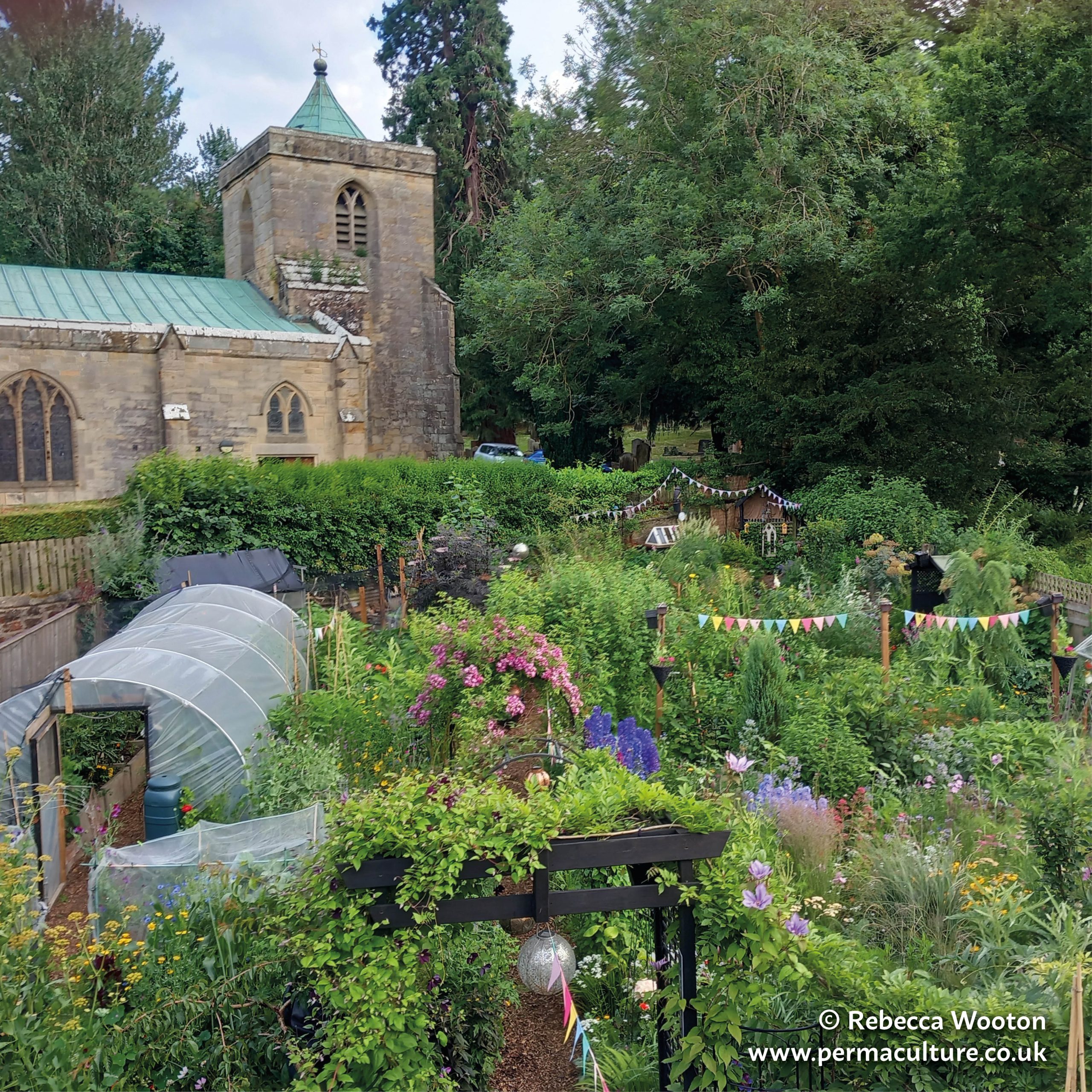

I’ve broadly categorized the main sources of mulch we produce in our 1500m2 garden.

Aquatic plants

I grow emergent wetland species such us cattails (Typha spp), sedges (Carex spp.) and rushes (Juncus spp.) on the banks of a small pond (6m x 3m), and within a grey water reed bed (1m x 6m). The pond also provides suitable habitat for hornworts (Ceratophyllum spp). a submerged rootless perennial that gathers on the surface en masse. This plant makes an excellent mulch being rich in nitrogen, growing very fast and is easy to position around the base of plants. The emergent species provide a good thick carbon rich mulch that helps to reduce evaporation on the terrestrial beds and I cut these back in the spring in case they are used for overwintering invertebrates. Aquatic plants are an excellent source of mulch as there are no issues with seed germinating amongst your land based crops.

Tap rooted perennial / biennials

Deep rooted perennial plants tend to produce a good amount of biomass, are generally drought tolerant and do not compete strongly with our crop plants. I have found native biennial weeds such as greater burdock (Arctium lappa), a very useful mulch plant with the gigantic leaves growing back very fast after a cut. Lesser burdock (Arctium minus), is also useful albeit to lesser extent. Although biennial, if you cut back these plants before flowering you can prolong their life, harvesting good quantities of seed free biomass. I do eventually allow some of the plants to flower and they are much loved by bees among other insects.

Comfrey (Symphytum x uplandicum), ‘bocking 14’, is a classic example of a deep rooted mulch plant. We have the plant scattered throughout the garden and planted in dedicated patches. The plants do require irrigation however and will only provide good leaf yields if grown on fertile soil. Peeing on the plants is recommended.

Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus), provide a great source of biomass. For a good tuber harvest it’s best to wait until the end of the season before harvesting the mulch. We can never consume as much as we produce of these tubers in the kitchen. I have found them to be much appreciated by our pigs and an excellent source of fresh winter food for our rabbits.

Leaves of greater burdock (Arctium lappa)

Nitrogen fixing trees and shrubs

These plants take a while to establish but make an excellent contribution. I’ve had good results from coppicing empress tree (Paulownia tomentosa), when they are 3-years-old and chop and dropping the soft new growth three or four times a year. I am expecting to also see good results from grey alder (Alnus incana) and Italian alder (Alnus cordata). I avoid using thorny nitrogen fixing trees and shrubs for this purpose. Annual trimming of shrubs such as autumn olive – Elaeagnus umbellata and broom – Cytisus scoparius also provides good quantities of mulch.

Click here for more info on nitrogen fixing plants.

Lawn and ground cover

One of my favourite sources of mulch is lawn trimmings. They are great for mulching potted plants or applying a mulch into tight spots. Mixed species lawns will contain a more diverse mix of mineral nutrients. Lawns including a legume such as white clover (Trifolim repens), can provide a nitrogen rich mulch. It’s a good idea to leave some of the trimmings behind to keep the lawn healthy.

Autumn leaf fall and herbaceous stem residue

The annual shedding of leaves from trees and shrubs in our garden make a great contribution to our mulch capital. Leaves can be cleared from paths, lawns and wildflower beds (as they will disrupt the growth in these areas) and concentrated where they are of benefit such as the base of high demanding fruiting shrubs such as blackcurrants or blackberries.

Herbaceous perennials such as lemon balm (Mellisa officinalis) and mints (Mentha spp). will provide dead stems annually. It’s always a good idea to leave hollow stems of some herbaceous perennials to remain for the winter as they are utilized by invertebrates for egg laying and hibernating. If the plant does not have a hollow stem it can be cut back and used for mulch. Fennel (Foeniculm vulgare), provides large quantities of biomass and as far as I can tell the stems are not utilised by any organism over the winter. In the vegetable garden all the remnants of my crops after harvesting go straight back to the surface for recycling.

Foeniculum vulgare and other herbaceous perennials

Tree prunings

Woody prunings from shrubs, trees and vines cut into small pieces (5-10cm) make good mulch in the mature areas of the forest garden with well established fungal soils specializing in breaking down the lignified woody material.

Living mulches

In the more mature areas of the garden where the trees have established (5yrs and older) I have dispensed with mulch all together in favour of ground cover plants that can be considered living mulches. Some the most successful perennial living mulches I have found that form good dense cover in the shade include bugle (Ajuga reptans), spotted dead nettle (Lamium maculatum), Caucasian stonecrop (Sedem spurium), perwinkle (Vinca major) and betony (Stachys officinalis).

Lamium maculatum spreading well under a mullbery (Morus alba)

Scaling up mulch production

In order to grow enough mulch to provide a water retaining, weed excluding barrier for my annual and nursery beds I would certainly need more space. A larger wetland area would be ideal, with aquatic species growing very fast and the seed bearing parts of the plants being non problematic to use on terrestrial beds. If you don’t have a reliable aquatic habitat, the next best option for growing quantities of mulch without irrigation and fertilization is probably grass.

During my next post I’ll be sharing a plan where using the lessons garnered from small scale systems, we’ll be growing mulch to support approx 670 fruit trees and 1360 soft fruit shrubs on a 5ha Agroforestry Project (design layout below).

Originally appeared at http://balkanecologyproject.blogspot.com/2015/03/growing-mulch.html

Paul runs the Balkan Ecology Project in Bulgaria with his wife Sophie Roberts and their two boys Dylan and Archie.