Below the trees, we have a rather mixed bag of species that are too small to be called trees, but too large to belong in the ground layer. Some are woody shrubs, some die down and leap back to considerable height every year and others climb up trees or supports.

Aralia cordata

Araliaceae

Udo is one of the most impressive sansai, growing from overwintering roots to a height of about 3m (9.8ft) every year. There are several edible parts: the roots, the young shoots, the pith of older (but still growing) shoots, the shoot tips and the flower shoots. All parts share a distinctive lemony-resiny flavour, which is strong enough to need tempering when prepared for eating. Shoot tips make great tempura and go well in stir-fries. The pith, with the bitterly resinous skin pared away, is usually soaked in water for a while to moderate the flavour, then sliced into salads, cooked with soy sauce and mirin to make kinpira or diced into a stir-fry. The flavour can also be moderated by blanching them in spring, and Stephen Barstow, in Around the World in 80 Plants, describes a minor industry sprouting udo roots in caverns under Tokyo. The large roots, which can be dug in the winter, have a milder flavour than the top growth.

Udo is hardier than its Plants For A Future entry suggests, growing well for me in Aberdeen, Stephen Barstow in Malvik and also in Finland. It is often sold in Europe as the cultivar ‘Sun King’ (a positive spin on its rather peely-wally yellow colour), which is less vigorous and somewhat less hardy. I prefer the wild type, but the cultivar might be better for a smaller space. There are several other closely related species. Manchurian spikenard (A. continentalis) is very similar and even hardier; my plant manages to set seed while my udo doesn’t. I haven’t been able to get hold of miyamo udo, the high mountain udo (A. glabra), but it also sounds promising. All udos tolerate a fair degree of shade, making them perfect for an awkward, shady corner in a garden, but they also revel in full sun.

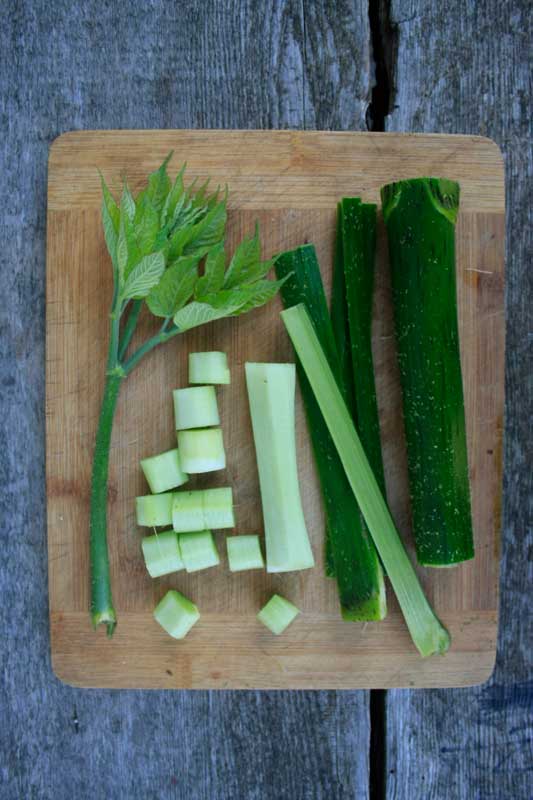

Alan’s brother at Cruickshank Botanic Garden, showing the size of udo

Udo pith and shoots

Aralia racemosa

Araliaceae

American spikenard is similar to udo and can be used in all the same ways. It is not quite so big, but still large, growing to about 1.8m (5.9ft). Its root has a liquorice flavour (and has been used in making root beer) and it is unusual in the family in that the fruit has been recorded as being used. I haven’t had a chance to test this myself as mine hasn’t set fruit yet, but North American foraging sites mention them being used for jelly, wine and raw fruit and say that they taste like root beer. It will grow in heavy shade if all you want is the roots and shoots, but it probably needs sun for fruit production.

Eleutherococcus sieboldianus and pubescens

Araliaceae

Ukogi, or five-leaved aralias, are spiny woodland-edge shrubs growing to around 3m (9.8ft). David Brussell reports the use of the shoots as tempura; mine has shoots that seem rather small for this but taste nice and stir-fry well. As well as E. sieboldianus, which is fairly widely available in the West as a hedging and ornamental plant (including in variegated forms), Brussell lists E. pubescens as growing in the same prefecture and at the same elevation, so it should be hardy too.

The heath family supplies a number of berry-bearing shrubs. All of them are acid-lovers that should never be limed. They generally have very small seed, sometimes like dust, which needs to be sown on the surface of an ericaceous compost and watered well.

Species in Vaccinium

Subgenus Vaccinium

Ericaceae

Don’t spend too much time learning the Latin names of the blueberries as the genus Vaccinium is ripe for rearrangement by botanists. The common names of the genus aren’t much better, with a host of regional British names for blueberries (such as blaeberries, billberries, huckleberries and farkleberries) applied unsystematically to a range of North American species encountered by colonists. Fortunately a blueberry by any other name tastes as sweet, and we’re more interested in the fruit than the names. Most blueberries are low-growing, but some deserve inclusion in the shrub category.

The best of the set is the highbush blueberry, V. corymbosum, which grows naturally in wet woods and pine barrens in eastern North America. It has become the basis of a major industry and widely hybridised, so that cultivars now have the best characteristics of several species. The berries are popular on cereal and yoghurt, in ice cream, in muffins and pies and as jam. They dry well and make an excellent fruit leather. The twigs and leaves (ideally with fruit attached) can also be dried and make a nice tea.

The biggest challenge is getting to the fruit before the birds. If they find your bushes you may need to net them, which is easy enough as they grow to 2m (6.5ft) at most, with most cultivars being smaller. Highbush blueberries grow in a wide range of habitats, from wooded to open and from wet to dry, so long as the soil isn’t alkaline. In the forest garden they will take moderate shade next to a tree. I have found that they will fruit quite well even with tall herbaceous vegetation growing up around them, which makes for an alternative method of hiding them from the birds.

Other woodland species worth growing include V. parvifolium, the red huckleberry/bilberry, which grows to 1.8m (5.9ft) in coastal forests from Alaska to California, and is described as ‘acid but very palatable’. V. membranaceum, the mountain or thinleaf huckleberry, grows in thickets and woodland edges in damp woods in Michigan and from Alaska to California. It reaches 1m (3.2ft) and the berries are among the largest and best-flavoured of all wild blueberries. V. ovalifolium, the black huckleberry, grows across northern North America in open woods and has a pleasant sweet flavour. It is taller than most, growing to 3m, and is particularly hardy.

More unusually, V. ovatum, the box blueberry, is an attractive evergreen shrub growing to 2.5m (8.2ft). Its berries are small, shiny, juicy and abundant but not very flavourful. The Caucasian whortleberry (V. arctostaphylos) comes from the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia. Its berries are also not as flavourful as highbush or thinleaf blueberries, but are juicy and refreshing, superior to the box blueberry. It grows to 3m (9.8ft) and has spectacular autumn colour.

Hablitzia tamnoides

Amaranthaceae

Also known as Caucasian spinach, climbing spinach is exactly what its name suggests: a tender leaf that grows as a climber. Although it comes from the Caucasus mountains, it has a history of being grown in Scandinavia, as told by Stephen Barstow in Around the World in 80 Plants. Scandinavian-origin plants are probably the best bet for growing in cool temperate areas.

It is possible to grow climbing spinach up a tree, but it takes a lot of patience. It doesn’t really like a lot of shade and it establishes much faster growing up a wall or supports in a sunny spot, in which situation it can easily grow to 3m (9.8ft). As well as the young leaves, which have a mild taste and can be harvested through much of the growing season, it produces a cluster of overwintering shoots at the base which can be harvested judiciously during the winter months.

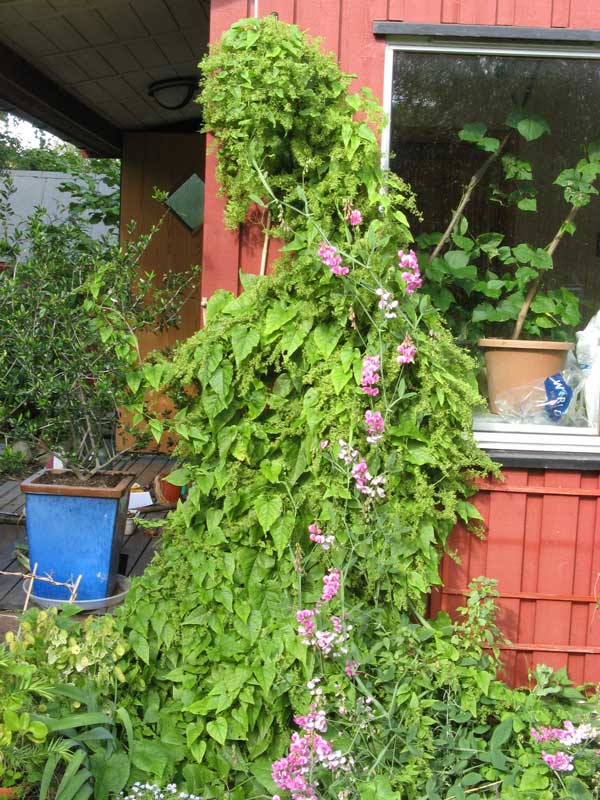

Hablitzia tamnoides scrambling up the south-facing wall of a house in Norway. The purple flowers are everlasting pea (Lathyrus latifolius).

Lonicera caerulea

Caprifoliaceae

As a large shrub with edible berries, the honeyberry is not what you expect of the honeysuckle family. It is very hardy and in recent years a wide range of improved cultivars have become available, but new growers often find them disappointing. There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, they grow slowly and take several years to come into production, so a little patience is needed. Then there is pollination. They are not self-fertile so two compatible cultivars are needed and since they aren’t widespread you can’t rely on plants in anyone else’s garden. They seem to go out of their way to avoid pollination, producing rather inconspicuous flowers in late winter or very early spring; the RHS recommends hand pollinating them with a paintbrush! Some people also report that the fruit tastes like turpentine.

Honeyberry flower

You can increase your odds by planting a number of different cultivars to increase the chance of pollination. Having other species of honeysuckle around might also help. If you have other early-flowering shrubs like willows around you’ll attract more pollinators, who might then also notice your honeyberries. The turpentine taste is more of a mystery. Both growers who said this had their plants in rather shady places so it might be down to not ripening properly, or it might be a case of different people tasting the same fruit differently. My berries, when I can persuade the plants to produce them, taste pleasant, rather like blueberries.

– – –

This is an extract from Alan Carter’s A Food Forest in your Garden, an informative guide for anyone wanting to create a forest garden, large or small. Packed with details on creating your own productive, edible paradise with multiple layers.

Alan studied forestry and has worked variously in forestry, gardening, conservation and greenspace management. He has been writing and teaching about forest gardening since 2011, having spent many years experimenting with it in his allotment in Aberdeen.