In some parts of the world, micro-agriculture has proven its worth throughout the ages. While designing the Bec Hellouin method, we were inspired by the most productive forms of traditional agriculture, the latest agricultural research, and permaculture. The techniques described in this manual are very efficient: Nature is incredibly productive!

Living with the Earth offers a modern and creative approach to designing microfarms, which can range in size from a few dozen square metres in the city to a few acres in the countryside. Permaculture microfarms are a profound mix of vegetable gardening practices from the past and professional farming techniques. Now, even with just a simple lawn to convert, we can reconnect with our farming ancestors and discover the joy of working by hand and consuming our production, even as a part-time endeavour in an urban environment.

Permaculture invites us to move away from denunciation and discouragement and enter into the realm of solutions. It is based on an ethic: Respect the land and all living creatures, share resources equitably. To better immerse yourself in the Bec Hellouin method, we invite you to read our previous book: Permaculture. Guérir la Terre, nourrir les hommes. It was translated into English with a new title: Miraculous Abundance.

We wish you many happy days in your garden!

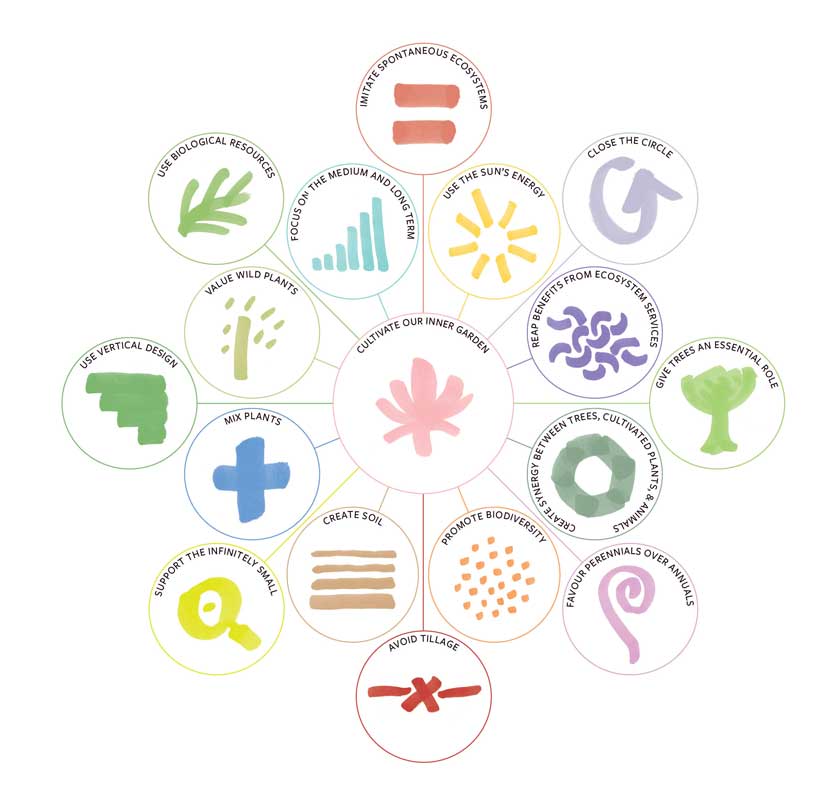

Our quick overview of the history of agriculture (see Living with the Earth: volume one) pointed out many pitfalls to avoid as well as possible solutions. Imitating spontaneous ecosystems seems to be the solution par excellence. Here we describe the essence of the Bec Hellouin Farm method. What follows are some important principles inspired by nature. They are the foundation of ecoculture as we understand it. All of the techniques described in this manual are inspired by it.

The 17 founding principles of ecoculture (above) will be enormously helpful when deciding to create an organic garden or farm. Readers, these tools are at your disposal: You can try them out and see their efficiency. Gardeners and farmers of the past millennia did not have access to such benchmarks, formalised and anchored in a scientific framework, but they did apply the ideas intuitively, and most often partially, in many parts of the world within traditional farming communities.

These principles are both easy to understand and relatively simple to implement. They lay the foundation of a framework for reflection but need to be adapted to each context. They therefore call on our observation and reflection skills, as well as our creativity. There is no ready-made recipe!

They also invite us to achieve a profound revolution in agronomy. This is a real paradigm shift, a 180-degree turn in relation to the practices that dominate production-driven agriculture. These major benchmarks can also lead us to revisit organic farming as it is practised today.

Ecoculture is an emerging practice. Distinctions between agriculture and ecoculture have not been fully delineated yet. The latter borrows from the best practices of the former, blending them into a new vision. Ecoculture remains largely unexplored, yet all of the favourable elements are united so that progress can be rapid.

We are now able to study most agricultural practices developed by humankind throughout the ages, on different continents. By studying them, we can discover remarkably ingenious techniques, edible plants with interesting properties, and simple and effective tools.

This rich and diverse heritage merits a merger with the latest advances in science and contemporary techniques. We live in a cognitively unique era. Our knowledge of biology doubles every five years. Let us dare to see far and wide: It is no longer enough to do as little harm as possible. We now must repair the damage inflicted on the planet. The information in this manual is fully in line with that ecological-restoration perspective.

Ecoculture can prompt an ascending spiral. It can nourish generations to come while healing the Earth – in small bits, garden by garden, slowly at first, then more and more quickly, as the collapse of resources makes the mutation more pressing and necessary. As we have suggested in our previous book, the very high productivity potential of ecoculture allows us to focus on small, intensely cared for spaces, freeing up vast areas that can be planted with edible forests or reverted to wilderness.

To our knowledge, there is nothing preventing this switch from agriculture to ecoculture. Its implementation could start today, everywhere. However, it will be necessary to revisit certain elements of the past and evolve the economic structures of our society, in particular the agro-industrial sector. Switching agriculture practices will require us to modify our eating habits. We will not be eating exactly the same foods if we want to live in a gentler way on the planet. Goodbye Kenyan beans and New Zealand lamb! Tomorrow’s food will be as local as possible. It will consist of fewer annual plants, cereals and animal products, and will consist instead of more vegetables, fruits, nuts, berries, and wild plants. It will be tastier, because it will be natural and fresh. This shift can only be beneficial for our health; we will be eating a diet closer to the one that sustained humans during the long evolution of mankind. This potential improvement in the state of health of our future generations will be one of the many positive results of this approach.

More broadly, the transition from agriculture to ecoculture invites us to rethink the entire organisation of society, starting from what constitutes its base: food production. The rise of micro-agriculture opens up the possibility of relocating food production to inner cities. This will diminish the need to transport goods and people. Localisation creates favourable conditions for the decentralised management of society, in which small-scale solutions are derived from the communities themselves. Experience from many different countries shows that this is the most favourable approach, whether for a transition to renewable energies, recycling, the creation of green jobs, economic, social and solidarity, or other needed transformations. At the local level, the creativity of civil society can fully express itself.

Ecoculture promotes local resilience, food security, and the energy autonomy of communities. It is a tremendous opportunity to move toward a truly sustainable form of society, which is the objective of permaculture. The shift from agriculture to ecoculture is much more than a technical revolution: It is indeed a societal revolution. Cultivating your own garden is a strong political act, in the noblest sense of the term.

At Bec Hellouin, where we practise market gardening, arboriculture, and small-scale livestock farming, we are going against the major trends in contemporary conventional agriculture in many ways:

We believe that the smaller and better cared for the cultivated area is, the more productive the farm becomes, while the conventional trend is towards expansion.

We work by hand and seek to free ourselves from motorisation, while conventional agriculture seeks to replace human labour with machines and high-tech solutions.

We are inspired by ancient practices, while conventional agriculture considers the past outdated.

We are ultra-connected to the latest scientific advances, while the world of conventional agriculture is often based on obsolete knowledge that is many decades old (in terms of soil, fertility, and biodiversity in particular).

We are inspired by traditional farming practices from the southern hemisphere, which Western agronomists have often disregarded.

The biggest difference is that we take nature as a model while contemporary agriculture deviates from it.

The transition to ecoculture comes up against a limiting factor, a major obstacle to overcome because it is located … inside our heads! It is very difficult, in fact, to deconstruct our preconceived notions of what agriculture should be and adopt a diametrically opposed vision. Since the Neolithic period, the natural environment is often seen as unproductive space populated by pests. Farmers tend to believe that bountiful harvests are obtained in highly controlled conditions with technologies that they employ, at the cost of a lot of effort or a lot of energy. Ecoculture offers an inverse vision: Each natural environment is a model of ingenuity and sustainability that can inspire us.

To switch from one notion to another, it is useful to ask ourselves about the link that unites us to nature. Who knows, maybe we need to look back deep in our memory, before the Neolithic period and the invention of agriculture, and rediscover what Gauguin was looking for while fleeing civilisation, the memory of a time when we walked naked in an untouched world, consuming the resources that Mother Earth generously offered?

This is an extract from Living with the Earth: A manual for market gardener – volume 1