Crop protection is not only about keeping pests and the weather from damaging our cherished fruit and vegetable plants, it is also a useful way of extending the season, ensuring abundant harvests and creating an ideal environment for growing healthy plants whilst encouraging and supporting nature. Protecting our plants using positive action is far more sustainable than ‘curing’ problems caused by pests, weather or poor soil, an attitude which is sadly endemic in ‘mainstream’ growing.

I grow most of my food crops in beds of about 1.2m (4ft) wide and varied lengths, mostly in blocks of different plants. I find that this method works extremely well because it is very easy to use effective crop protection.

In rows, I can open up one side of the cloche, flip the covering over and easily reach everything. Growing plants in blocks like this is not ‘monoculture’, there is a huge difference between the large scale farming of acres of single crops and domestic growing of perhaps 20 cabbages in one place. Also in some cases, such as with most sweet corn, it is absolutely necessary to grow them together so that they can pollinate each other. This works well for many perennial plants too, in particular those that need protection from time to time, such as strawberries – it is far easier, time effective and more attractive to net a bed of berries than individual plants.

There is a lot of interest in companion planting as a form of crop protection, which in many ways should be a brilliant idea. However in my experience, growing carrots with onions has not deterred carrot root fly (though using enviromesh is effective). Pests are rather deter-mined and seem almost to enjoy the challenge of navigating anything I have planted with the intention of confusing them – watch cabbage white butterflies on a summer’s day! I have tried ‘sacrificial’ plants, but again these have not deterred the pests from visiting my main food crops.

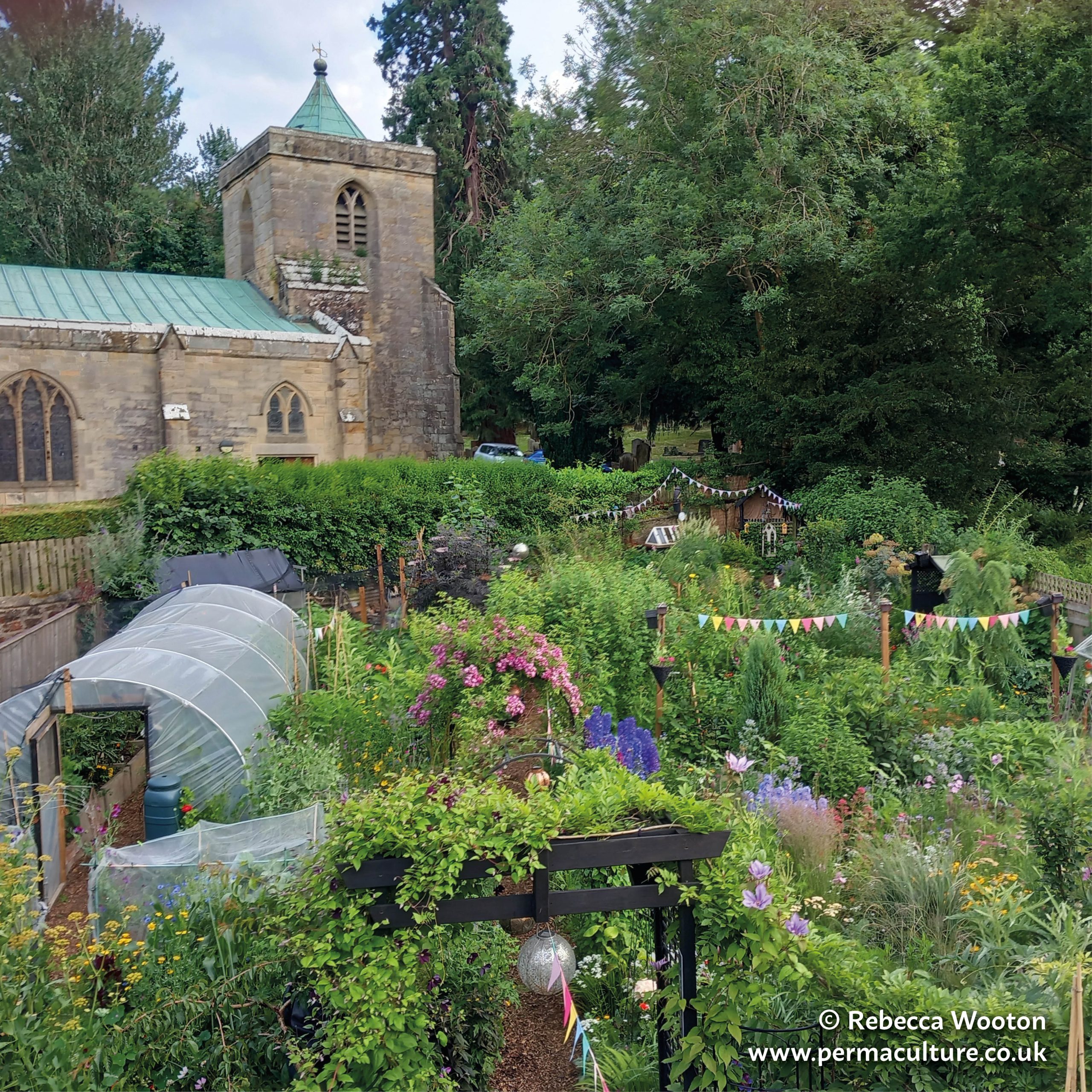

I see companion planting as a supportive role in the garden, encouraging predators (ladybirds, hover flies) and other beneficial insects such as bees. Some companions can help enrich the soil, or encourage good composting or even increase the potency of crops planted with them. Others attract insects (such as moths) which in turn provide food for wildlife (bats) which help to create a diverse, beneficial ecosystem within the garden. My polytunnel, allotment and garden are full of flowers to attract beneficial insects, some for food and also for my own pleasure. As the head gardener at Chalice Well, Ark Redwood, says that flowers are ‘food for the soul’.

The key here is to encourage beneficial wildlife and obviously I do not encourage pigeons, deer, rabbits or other veg-loving animals. I like to create habitats for nature in my growing spaces but not on the beds where I grow my vegetables: after all, most predators cover a significant distance when foraging so they don’t necessarily want to live adjacent to my onions. A ‘bug motel’ is very likely to provide five star accommodation for slugs and woodlice rather than anything helpful for my vegetables here in Somerset, whereas a mulch of well rotted compost on the surface of my beds really does provide a habitat for beneficial creatures, including spiders and black beetles. I also have shelters for toads and hedgehogs in the wild edges and corners.

The key to healthy plants and good growing is a fertile, healthy soil. I grow organically, using no dig methods so my plants are growing in soil with good structure and a healthy population of beneficial soil flora and fauna, including mycorrhizae. The surface mulch of well rotted compost, just 2.5-5cm (1-2in) a year, feeds the soil and plants, reduces the need for watering and provides a whole ecosystem for a vast number of creatures. I keep the growing area weed free so that the plants are not competing with the weeds and also to reduce habitat for pests. It is easy to hoe and maintain the beds and the earth paths. I can focus on the needs of my plants rather than dealing with problems.

Observation and good maintenance is a crucial part of crop protections and a pleasure too. I practise an every-other-year crop rotation for my annual vegetables, which works fine and is far more practical in smaller domestic gardens than a three or four year one. Crop rotation is practised to discourage the build up of pests in the soil. Regular observation can help you notice an aphid attack, a need for more or less water, or to spot any early signs of disease. Pruning at the right time can make the difference between an abundant crop and a mediocre one. Good tomato maintenance under-cover can help protect the plants from early blight attacks – remove the lower leaves after the first truss has fruited and always water the soil, not the plants themselves.

Sowing and planting at the right time is crucial. Every year the same people on my allotment sow their runner beans far too early and they are then killed off by frost. It is possible to protect them using fleece but even that is unlikely to prevent problems for such frost-sensitive plants: sow at the right time for your area and put the young plants out when the last frosts are over. Although enviromesh can help to protect plants from flea beetles it is more effective to sow and plant out susceptible vegetables after the flea beetle season has passed.

I use many different types of cloche hoops, some specifically made for the task and others upcycled. In the kitchen garden I manage, we use hoops made by a local blacksmith – two different sizes: both are 1.2m (4ft) wide but one is the right height for lower crops such as cabbages and the other is a taller one, just right for purple sprouting broccoli and Brussels sprouts. They have long straight sides which can be made higher and lower, with bars across each end that hold the netting taut. These hoops have a huge lifespan and are easy to repair. They are without a doubt one of my key gardening tools: so simple, easy to use and extremely effective with minimal impact on the environment after they are made.

You can buy hoops and fruit cages online but it is easy to make hoops using old water pipe and bamboo or wooden stakes. The stakes are pushed into the ground quite deeply to stop the structure from falling over, the pipe is then cut to size and slotted over the stakes. Young hazel and birch make beautiful hoops, trimmed so that the twiggy parts do not snag the netting or mesh.

Other hoops are made from 5mm wire, bent over. I have experimented with old tent poles, cut to size – these fall over if they’re too large but are good for smaller cloches.

Coverings are all manufactured using plastics, but with care they will last for many years.

Fleece protects from some pests, late frosts, wind, the extremes of weather (to a degree), cold summer spells, birds and discourages some other animals.

It is worthwhile buying a good quality fleece which will last and withstand wintry weather conditions. The cheaper sort easily shreds and is unlikely to last a year. I buy 30gsm weight. It is easy to cut to size and can be spread across young plants in the spring to protect them, therefore allowing earlier sowings of some varieties. Keep the fleece taut – the plants will push up and grow, but will be damaged by fleece flapping in the wind. I use large stones or special clips with tent pegs to secure the fleece. It is important not to pierce the fleece as it will tear and shred.

Fleece will help bring plants on a bit faster, perhaps by a couple of weeks or more, especially during a cold spring. It is not uncommon in the spring to see me sprint up to my allotment with a few bundles of fleece to tuck up my emerging potatoes if there is a warning of a late frost!

Netting protects against birds, cats, squirrels, deer, rabbits, chickens, ducks and badgers to a degree (although they will dig under it). Butterfly netting also protects against cabbage white butterflies. I secure both types using tent pegs.

Bird netting has larger holes which has the advantage that insects, including bees, can fly through. During the harsh winter of 2011, I discovered that brassicas protected by a cloche with bird netting survived with significantly less damage than those exposed to the full effects of the snow and cold, most likely because they were not bearing the full weight of the snow and also because it lessened the impact of the wind. It is excellent to use on large fruit cages and frames.

Butterfly netting is very effective against butterflies, so long as no leaves are touching the sides. As it does not allow beneficial insects to pass through, do not use it on anything that requires insects pollination.

Always ensure that netting is well secured and that birds can not get in. They may become tangled up in the netting and can die. A solution I have found is to pull the netting back when I am working, which allows birds to forage amongst the plants, benefiting bird and plant, replacing it before I leave. Naturally I don’t do that during a period of intensive butterfly activity!

This protects against carrot root fly, aphids, flea beetle, cabbage white butterfly and leek moth.

I either spread this across the plants or over a cloche frame, depending on circumstances. In order to protect your crops from tiny insects it is important to secure it with stones or clips/tent pegs so that they can not get in underneath it.

I also use enviromesh to protect my small cherry tree from birds and also throw some over some soft fruit bushes in the garden to deter birds. An advantage is that birds cannot get tangled up in it or peck through the tiny holes.

In the greenhouse, I place smaller pieces over young brassica plants. Cabbage white butterflies will even fly through open windows to get at brassicas.

A disadvantage of enviromesh is that it blocks around 30% of the light, so should only be used when absolutely necessary to allow full growth.

This can easily be found rather than bought – ask on Freecycle or similar.

Use leftover pieces from covering polytunnels, builders’ polythene or sheets from large items such as mattresses. Use polythene to make mini-greenhouses, cold frames and over cloche hoops for a smaller version of a polytunnel. I have grown salad all winter at my allotment using a piece of polythene weighed down with stones over hoops.

These are usually more permanent structures which create an environment for year-round growing. I have electric heat mats in my greenhouse to help raise plants and protect them against the cold.

The polytunnel has transformed my growing life, providing my family with an increased choice of vegetables all year round – and a place to dry the washing in the winter! The polytunnel is not frost free; it protects the crops from the extremes of winter weather, in particular harsh wind. Always make sure greenhouses, polytunnels and cold frames are well ventilated to create a healthy environment free from damping off, mildew and other problems.

There are many possibilities here, including permanent solutions such as planting a wind break. This is often not practical in smaller, domestic spaces or allotments where a good solution is to use a sturdy frame of climbing beans (I use foraged hazel or thicker bamboo stakes) and to plant more wind sensitive plants behind it.

Stakes and supports play a part here too. It is a pleasure to make beautiful, intricate woven plant supports from foraged hazel and birch if you can find it (always with the owner’s permission, of course) or support your local willow craftspeople by buying their structures or attend-ing a workshop. Other alternatives include strong bamboo, wooden posts or metal structures which are widely available – hand made ones are more expensive but support local artisans and should last a lifetime.

This year I discovered that very twiggy hazel which still had leaves on, protected peas not only from the wind but also from pigeons, which stripped peas growing up less twiggy and leafy sticks. I have never known pigeons destroy a whole crop of peas in a weekend before … there is always something new to learn in gardening.

For the past two years I have used pheromone traps to deter leek moth with success and next year I will be introducing a bought-in predator into my polytunnel to target red spider mite which was unfortunately introduced when I bought a cucumber plant from a garden centre. As I haven’t used them or nematodes yet, I can not comment on their effectiveness.

Stephanie Hafferty is a no dig gardener, writer and author of The Creative Kitchen and coauthor of No Dig Organic Home and Garden.