In the foothills of the Himalayas in northern India, a certain tree has long graced the region with its miraculous fruit. Hanging from its wiry branches are clusters of ribbed pods, each a foot in length. These pods, or drumsticks, have attracted the attention of mankind for millennia, and for good reason.

While the aptly named Drumstick tree has a rather slender appearance, it is anything but frail. A tropical native, this prolific powerhouse has spread its roots across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Caribbean. And now, it seems to have anchored itself in American soil.

Part of a new wave of exotic vegetables, Moringa oleifera (MO) is a botanical platypus. A member of the order Brassicales, it’s a distant relative of both the cabbage and papaya. Its roots taste so much like its cousin horseradish, that it’s earned the title ‘horseradish tree’. Its fruit, a popular Indian vegetable, looks like a cross between an okra and a pole bean with the flavour of asparagus. Its cooked flowers mimic mushrooms in taste, while its leaves hint at spinach and lettuce. Its immature seeds are used like peas and if fried when mature, resemble peanuts.

Moringa root

In fact, it’s hard to find a part of Moringa that isn’t edible. Even the bark is sometimes taken internally for diarrhoea. But that doesn’t come as a surprise to the locals, who consider it a living pharmacy. Moringa has proven to be a multipurpose arsenal that dispenses some of the best secrets nature has to offer. For centuries it has been used in Ayurvedic medicine to treat a host of ailments including anaemia, bronchitis, tumours, scurvy, and skin infections.

Drought hardy and disease resistant, MO is a godsend during the dry season, when little food is available. The fresh leaves and branches serve as an excellent source of forage. Indeed, a Nicaraguan study confirms MO’s ability to boost milk production in cows without affecting its taste, smell, or colour.

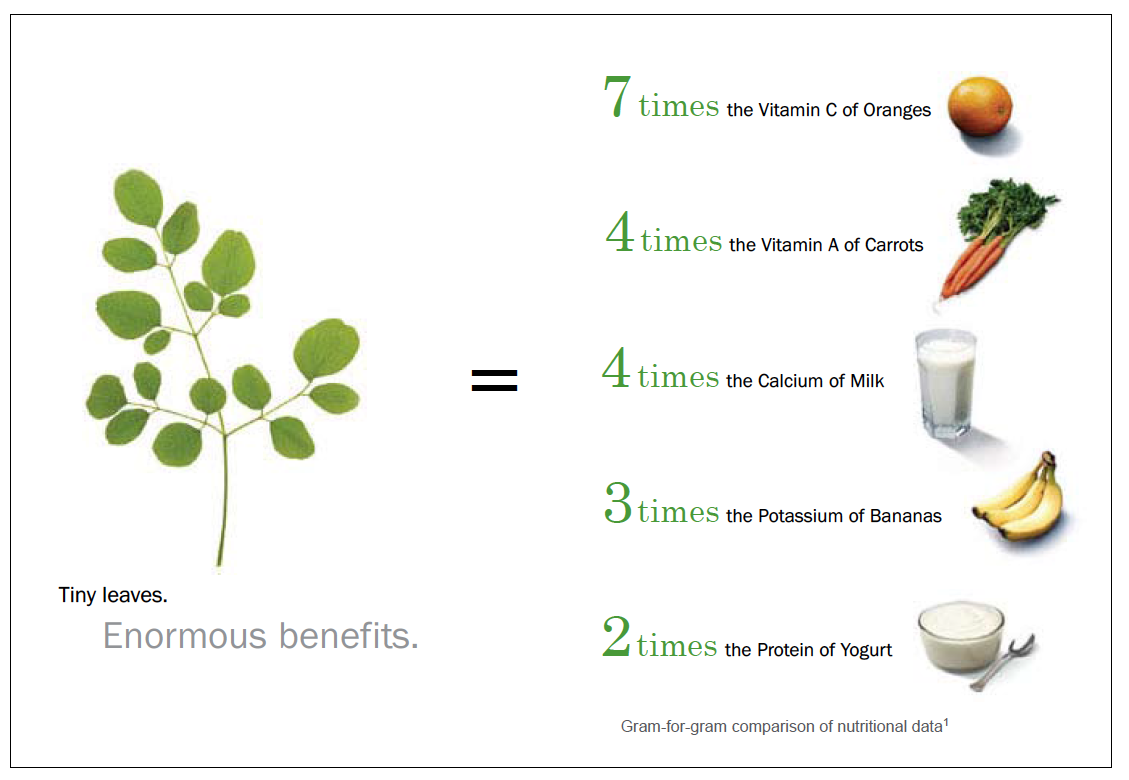

The leaves offer a spectrum of nutrition, rich in vitamins A, B, and C, as well as protein, calcium, and iron. They are so nutritious in fact, that they contain more vitamin A than carrots, more vitamin C than oranges, more calcium than milk, more iron than spinach, more potassium than bananas, and more protein than either milk or eggs! A traditional item in pickles and curries, the raw leaves are also perfect for salads.

As a result, Moringa could play a key role as a wholesome food source in impoverished nations, where malnutrition is often rampant. The World Health Organization has stressed the importance of amino acids and protein for growing children. Luckily, Moringa leaves are rich in these nutrients, with the added benefit of omega-3 fatty acids and a host of protective phytochemicals.

When mixed in with different cereals, children regained normal weight and health status in 30-40 days, while the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) recipe for malnourished children took 80 days, double the difference.

“[It] is a very healthy satisfying food that meets all nutritive needs. It is cheap to produce, can be cooked or eaten raw, sold in the market, or dried as a powder to be sold over long distances,” added Nikolaus Foidl, a world leading agricultural researcher on Moringa.

Foidl has been studying the tree for over a decade in conjunction with the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart, Germany. He has traveled to many countries, including Senegal, Honduras, Guinea Bissau, and Argentina, promoting the miracle tree’s cultivation by working with the locals.

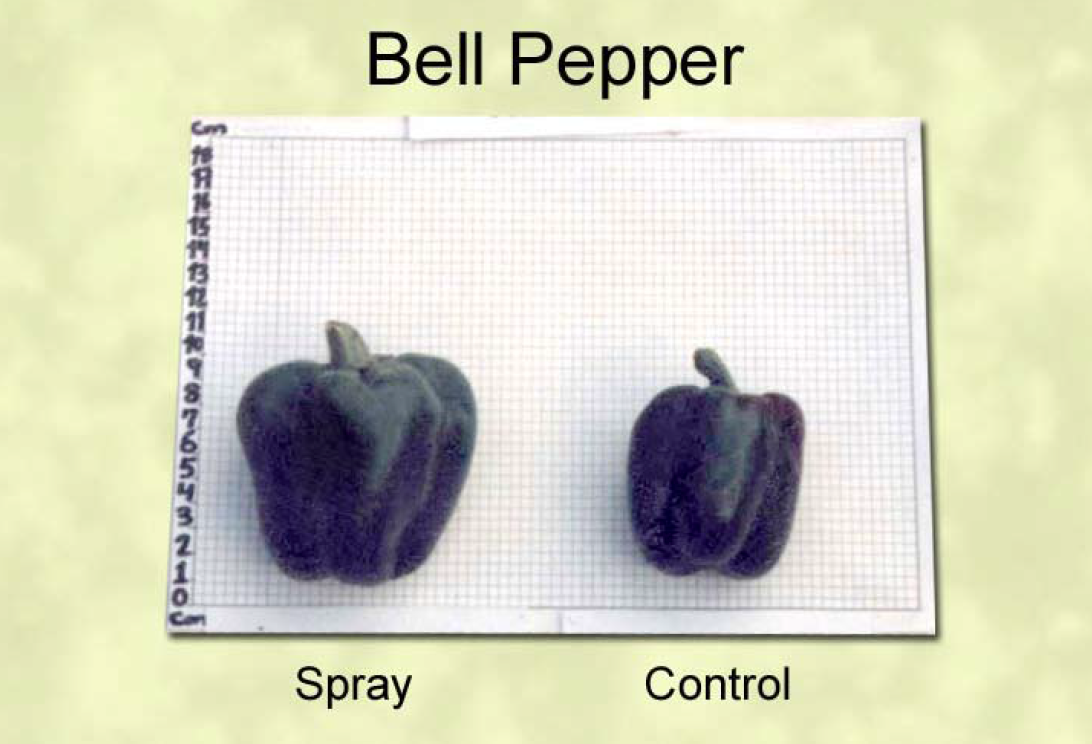

In Nicaragua, he helped farmers utilise the leaf extract as a growth spray for other crops.

“Moringa leaves contain the growth factors gibberellin, kinetin, and some lower levels of auxin. We got up to a 25% increase in sugarcane and turnips, onions and radish.”

Such a bountiful increase should not be ignored, especially in areas where food shortage is an issue. Foidl, who has the financial support of the Austrian government, first came across the tree by accident.

He recounted, “By chance, I had a Jatropha plantation with rows of Moringa as windbreaks and the damn cows were always breaking down my fences to get to them. So I wondered, what is so special about this tree that the cows are willing to risk injury?”

That question has now led to a new understanding of MO’s multifaceted potential. As a vigorous hardy grower, it surprisingly does not require much water or soil nutrients once established. This makes it one of the most valuable tropical trees in terms of overall utility.

Like the leaves, the flowers too are edible when cooked, packed with calcium and potassium. As a bonus, they are not only incredibly fragrant, but also support native bee populations.

MO roots and bark, on the other hand, are used with caution. The bark contains the toxic chemicals moringinine and spirochin which can alter heart rate and blood pressure. However, they do show promise in the medical field. The inner flesh of the root is less toxic, and those of young plants are picked for a hot sauce base while the resin is added as a thickener. Interestingly, blue dye can be obtained from the wood, which is also used in paper production.

But if Moringa were a magician, it has certainly saved its best trick for last. The famed drumsticks contain all nine essential amino acids that humans must obtain exclusively from their diet. Often, they’re chopped into logs, boiled, and split into thirds lengthwise. The fibrous rind is inedible – rather it’s the soft jellied pulp and seeds that are sought after. These can be scooped out or scraped away by the teeth.

Hidden within the drumsticks are even more remarkable seeds. Loaded with protein, they also contain special non-toxic polypeptides that act as natural Brita filters. When ground into powder and mixed with water, they cause sediments to clump together and settle out. Then when strained through a cloth, they provide cheap access to clean water. Amazingly, just two seeds are enough to purify a dirty litre.

“It has been widely used at the village level in Africa to transform river water into drinking water,” shared Foidl. “I had a project working with the seeds in a wastewater treatment plant in Nicaragua (wastewater from 4,000 people). It was very effective – about 99.5% separation of turbidity in 30 minutes.”

In turn, the seeds themselves yield a valuable yellow oil called ben oil. Sweet, clear, and odourless, it doesn’t spoil easily – perfect for perfumes, cosmetics, and lubrication. It has also found use in cooking due to its high levels of healthy unsaturated fats.

For such a versatile tree, it’s almost hard to believe that Moringa is easily grown via seeds or cuttings. Foidl remarked, “It grows virtually better than willow.”

As agriculture becomes more expensive, managing the long-term productivity of the land is essential. Moringa solves this issue through a practice called high-density planting. The trees are grown closely together to increase the yield per given area, while at the same time reducing the need for herbicides. Because MO grows rapidly, it crowds out and suppresses neighboring weeds.

“The optimal density is 1 million plants per hectare (10 x 10cm spacing), where the losses of plants per cut are around 1% and the losses are compensated through vigorous sprouting,” explained Foidl. “Moringa is cut at a height of 15 to 25cm for vigorous regrowth.”

Moringa just before harvest. Foidl either harvests at 35 days of growth or 75.

Moringa harvested on rotation

This practice allows for cutting every 35 days, totaling 10 harvests per year. In fact, 120 tons of dry matter can be harvested per hectare a year, 10 times more than corn and several times more than soy. As a result, there is a constant supply of fresh food, with little need for storage.

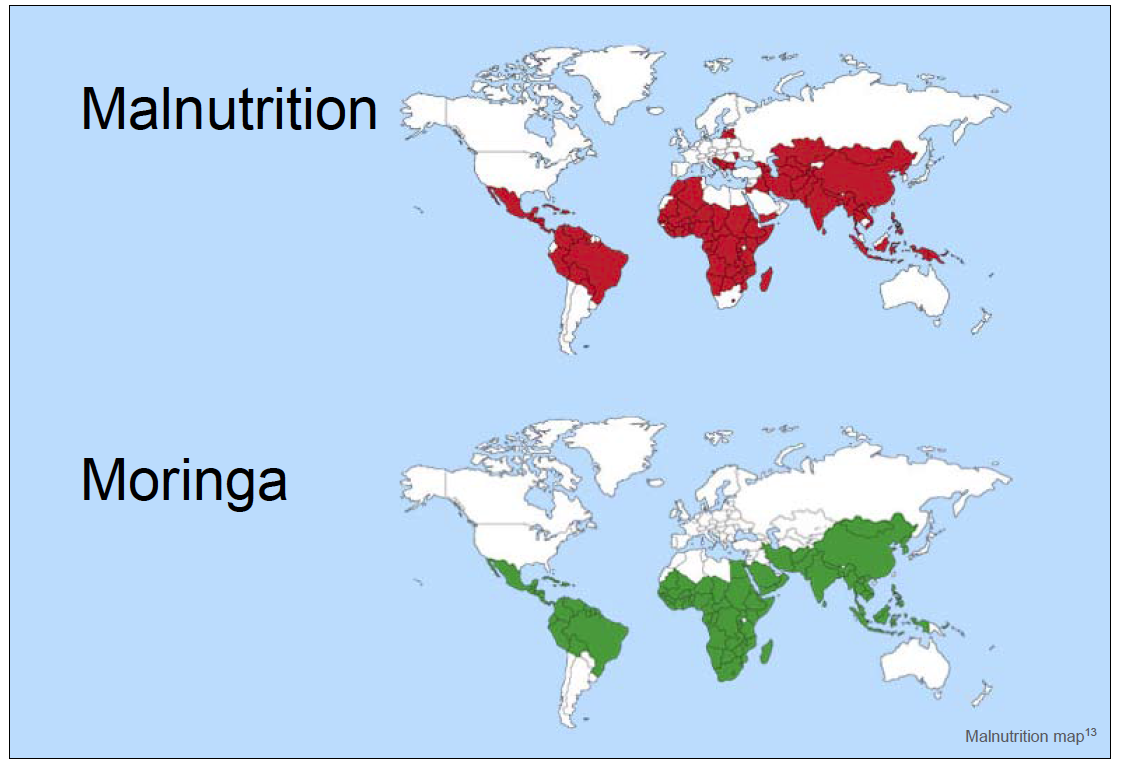

Moringa is in a unique position to address the issues of hunger, malnutrition, poverty, and lack of clean water all at once, something no other plant can boast. It is even more valuable considering it is found widely throughout the tropics, in the regions where it is needed most, making this ancient tree a true modern day miracle.

Moringa’s growing regions and regions of malnutrition

About the Author: Ansel Oommen is a garden writer, citizen scientist, and medical transcriptionist whose works have been published in magazines such as Atlas Obscura, Well Being Journal, and Entomology Today, among others. Discover more at www.behance.net/Ansel.

All images thanks to Nikolaus Foidl apart from Moringa root, thanks to Crops for the Future.