Just imagine being able to step out of your back door each day to pick fresh strawberries and red currants to sprinkle on your breakfast, or to gather salads and edible flowers for a large salad lunch, or imagine being able to harvest fresh vegetables just a few paces from the kitchen door each evening to add to your supper.

This is the lifestyle that I’d become accustomed to in my old house before we moved to a new town just three months ago. In our small garden – just 30 x 25ft – we harvested a diverse range of fruits, vegetables, herbs and edible flowers (see below for a full list).

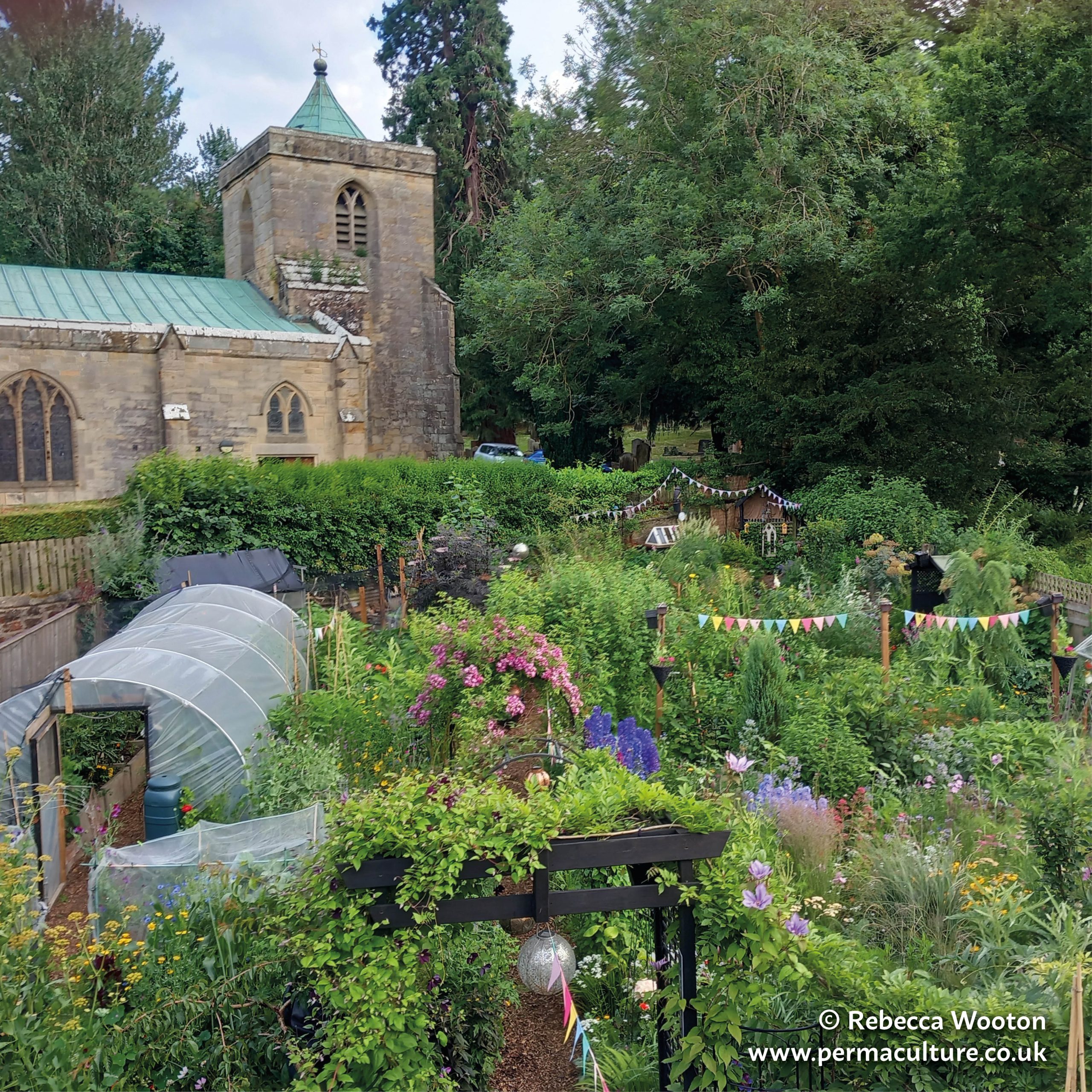

In order to get such an abundant and diverse yield from such a small space I applied some very helpful permaculture strategies.

It’s funny to think that despite all our human accomplishments we owe our existence to a six inch layer of topsoil (and the fact that it rains). Soil is everything; without it, we wouldn’t be able to grow the food we need, and a rich, fertile, and deep soil is the key to higher yields.

In my garden, in order to get a really deep soil, I created two 5x5ft raised beds using reclaimed scaffold planks to a height of about 2ft and placed them in the sunniest part of the garden. I filled them with a bottom layer of wood chip, then a mix of top soil and manure. Initially, the wood chip was only used to help build up the biomass (and it was just what we had to hand for free), but I later happily realised that as the wood chip broke down, the mycorrhizal fungi in the wood spread throughout the beds, transmitting nutrients to the roots of my vegetables as it went. This certainly helped to improve yield.

Once these beds were established, I never walked on the soil so that it didn’t become compacted, and I didn’t ever do any deep digging in it, to enable the worms and micro organisms to do their job in tunnelling and bringing air and nutrients to the plant roots. I also made my own compost from kitchen scraps and my own chickens’ manure, and used this compost as a mulch on the beds each spring and autumn. This way I could add nutrients to the soil on a regular basis to help keep up yields.

From these two modest sized beds I harvested a good yield of vegetables all year round to supplement our family meals.

The shape of your beds can have an influence on yield. If your raised bed is more dome-shaped with sloping sides, you are effectively gaining more surface area for more growing crops in the same footprint. For example, if your bed is 5ft wide across the base, it might give you a 6ft wide arch of soil. This also gives you the opportunity to create little micro-climates that favour certain crops, as some prefer areas that are shadier during the day, and others prefer warm sunny conditions.

When I had the opportunity to create a new bed in my garden, I chose to create a more dome-shaped bed, with old bits of chestnut on the edges to help contain the soil. Along the south facing edge I grew asparagus, on the northern edge I grew wild strawberries, and in the slightly domed middle, I grew annual crops such as chard, kale and beans.

The wild strawberries did particularly well, and were easy to pick as they leaned out into the path, and I remember enjoying good yields of chard and beetroot in Summer and kale through the Winter months. The asparagus was still quite immature when I moved away, so I cannot 100% sure that I would have had abundant yields from this crop, although even in it’s immature state (it was only two years old) I did get a modest yield.

Another example of growing crops in domed beds is called ‘hugelkultur’, developed by Sepp Holzer, where fertility is increased with the piling up of large amounts of biomass, increasing surface area and yielding greatly in a relatively small space.

Traditionally, vegetable crops are grown in rows, but this does not make the best use of space. You don’t find any rows in nature, where to make maximum use of any bare ground that becomes free it fills the space with plants in a roughly tessellating pattern. So to mimic this and to get maximum yields, it’s best to stagger your plants by arranging them in triangle formations. For example when I plant out broad beans and the packet advises leaving nine inches between plants, using a dibber, I mark out a triangle pattern with the corners nine inches apart and plant each bean in the holes. This means you get around 10% more crop in the same amount of space.

I’ve also learned from experience not to pack my plants too tightly, as this can mean they have too much competition for nutrients to reach their full size, and makes them more susceptible to pests too.

In a natural forest you’ll find plants colonising all layers in a three dimensional space, all the way from the ground to the canopy. We can mimic this in the garden by ‘stacking’ crops in multiple layers, rather than in only one dimension as mono-cropping does. In my garden I used this principle in different ways:

In my raised beds, I trained vegetables such as beans, peas and cucumbers up poles or trellis so that I could squeeze even more lower growing veg such as chard, salads or beetroot in between.

In the rest of the garden I grew fruit trees, shrubs and climbers, mimicking a natural forest with it’s different layers. For example I had strawberries on the ground layer, currants and raspberries in the shrub layer, and apple and pear trees in the canopy. I also had wineberries, loganberries and bayberries trained up the fences, and I used hanging baskets and tall pots to grow strawberries in.

A ‘guild’ is a group of plants that benefit each other, and by planting them together you can save space and increase your yield. For example I used the classic Native American combination, the ‘three sisters’ in my garden; sweetcorn, climbing beans, and squash. The strong sweetcorn stalks provide support for the beans to climb, while the beans fix nitrogen into the soil providing greater nutrients, and the squash grows between them all, helping to keep moisture from evaporating from the soil and to suppress weeds. I also had nasturtium winding it’s way through the crop. You can find a useful guide for companion planting here. Other combinations I’ve tried:

* Climbing beans with nasturtium spreading across the ground between them, which helps attract black fly away from the beans.

* Sowing radish and parsnip together so that I can harvest the quick yielding radish before the parsnip gets going.

* Sowing blocks of carrots and onions together so that the onion smell deters the carrot fly.

* Creating a jumble of various herbs and veg together to create a Polyculture to confuse cabbage white butterflies and other pests.

With successional planting you can grow more than one crop in the same space over the course of a growing season. My experience of the UK climate (living in the South) showed that I was able to grow up to three different crops in a single area over the course of a year. For example I would start with an early crop of purple podded peas, followed by a quick crop of summer salads, then in autumn I’d sow a crop of broad beans to overwinter.

The trick is to use fast maturing varieties, or sow lots of things in modules so that they are ready to go as soon as they are transplanted, and to replenish the soil after each crop is harvested with a fresh mulch of compost.

Getting to know your garden’s micro-climates helps you to find the best spots to grow crops for a longer growing season. I put my raised beds in the sunniest part of the garden so that it would warm up faster in spring and stay warm for longer in autumn.

Other ways to extend the season include using a cloche over your crops to create a more sheltered environment, and growing seedlings in modules on a windowsill or in a cold frame so that as soon as the weather is warm enough you can plant them out and grow them on quickly, ahead of those sown outdoors. Putting black plastic over the soil in nearly spring helps the soil warm up quicker so that warmer loving crops do better, sooner. I didn’t have space for a polytunnel or greenhouse in my small garden, but one day I’d love to have one so I can extend the growing season even further.

It also helps to get to know your plants. I discovered that a variety of kale called Ragged Jack (also known as Red Russian) was an ideal crop to overwinter, and as soon as the days started to get a bit longer in the new year it would reward me with an abundance of new leaves and tasty flowering shoots, a bit like Purple Sprouting Broccoli. I also discovered a perennial broccoli which was very quick to produce white florets in early spring.

Perennials are very useful in the garden because they yield greater quantities year on year, and are quick to get going early in the season. It’s always nice to harvest rhubarb and red currants, when other annual crops are still in their modules. Sorrel is useful perennial that I enjoyed harvesting for early salads. I would have liked to have ransoms (wild garlic) growing under my fruit trees as they yield delicious leaves and flowers in early spring before the canopy closes, but alas I had no room. Perhaps I’ll try growing them in my new garden?

You can increase the value of your yield, by choosing to grow crops that are expensive to buy in the shops, such as organic asparagus, blueberries, potatoes and tomatoes, This means that each handful of crop that you harvest is worth more in terms of cash value, saving you more money in the shops – and there’s something rather satisfying about that!

It’s also rather satisfying to be able to harvest things super-fresh, such as salad leaves or raspberries that quickly deteriorate when bought in plastic packaging. And it’s hard to put a price on a prickly cucumber still warm from the sun, and a variety that isn’t even available in the supermarket.

This is a permaculture principle that amuses me, and stretches my mind to see the garden as more than a set of crops to weigh out in the kitchen. Permaculturists tend to argue that there are other slightly less material yields to be found in the garden system. For example it’s hard to quantify the enjoyment I get from watching it grow and how this feeds my sense of wellbeing, or how it provides me with gentle exercise while enjoying the sound of birdsong, or how sharing a glut of courgettes can help build community relations! These can all be counted as a yield and I find it fun to think of life in this way.

This article originally appeared at: http://permaculturedesigner.co.uk/9-permaculture-tips-for-increasing-your-garden-yield