Permaculture, a contraction of permanent agriculture but also increasingly permanent culture, means working with natural forces like the wind, sun, water, the forces of succession, animals and other ‘natural’ energies. These permaculture designs provide food, shelter, water and meet other needs required to build sustainable communities with minimum labor and without depleting the land and bioregional, regional, national even global ecosystems. That is the ideal: stability, biodiversity, and the seventh generation principle. It is a vision of a whole culture including agricultural systems that provide for the needs of human beings without damaging the ecosystems in which we live. The seed thoughts are: abundance, thriving ecologies, biodiversity, stable and peaceful cultures and an understanding of our deep interdependence as a species.

We live in a world full of natural forces or laws but are they purely ones we learn about in our physics classes at school? i.e. Isaac Newton’s Three Laws of Motion, which describe basic rules about how the motion of physical objects change or his ‘Law’ of Gravity plus the addition of Einstein’s theory of general relativity which provides a more comprehensive explanation for the phenomenon of gravity?

Yes and no.

We know that gravity determines that objects fall to the ground, that water runs downhill, that moving inanimate objects downhill takes minimal energy, even that buildings are designed using the effects of gravitational forces using compression that holds them together and helps anchor them. We therefore design systems that take advantage of slope on a site when placing water catchment systems as well as adding swales to harvest both water and other nutrients and when moving materials around. If we want to reforest a hillside by optimising natural regeneration, we plant at the top of the slope, allowing trees to seed downhill. We also consider fencing out browsing animals like deer, certainly until the saplings get away.

We plant wind breaks to create microclimates and site our houses, structures and gardens to take advantage of their shelter. We site tender plants in microclimates out of the wind (and possibly the most savage noon-time sun). We site wind turbines on windy ridges for maximum efficiency and we site solar panels in the sunniest places to generate electricity and heat water.

These examples are common sense but it is surprising how great the temptation is to sometimes ignore that sense when you have big dreams!

We also learn in our biology classes about natural forces like:

Geotropism – the phenomena of plant roots growing downwards.

Phototropism – the phenomena of plants growing towards the light.

Hydrotropism – the phenomena of plant roots growing towards water.

As permaculture designers we would be stupid to try and argue with these forces, rather in our designs we seek to enhance them. For instance, crowding light loving plants into a low light, cool temperate forest garden in stacked layers and expecting them to grow into healthy specimens is arguing with phototropism. Instead, we want to promote optimum conditions for healthy plant growth by planting plants further apart than we would in the tropics or subtropics.

Our basic science education teaches us about natural forces and help us to understand how to recognise forces at work and work with them but permaculture design is more than the grasp of physics. By observing nature we can learn from its patterns. We learn about natural succession in a woodland or forest. A tree falls in our local forest and light comes into the canopy. What grows there and in what order? By learning from protracted observation, we can mimic this natural succession in our gardens, substituting edibles, medicinals and fibre plants for purely natives to provide for our needs in the niches that will most suit them. We are mimicking the wild plants and trying to create as low maintenance, peri-wild and healthy guild of plants as we can whilst being mindful of the yields we are seeking to achieve.

Animals too can help us understand our landscape. If cows and sheep are allowed to graze over an adequate, biodiverse area they will naturally select the plants that help them maintain health. By observing what they browse we can develop biodiverse pastures with the right balance of grasses, herbs and other medicinal plants to enable them to stay in good condition. By grazing animals on rye monocultures we reduce their immunity, necessitating the need for antibiotics in their feed, drugs that ultimately taint their milk and meat and create an immunity time bomb for human health.

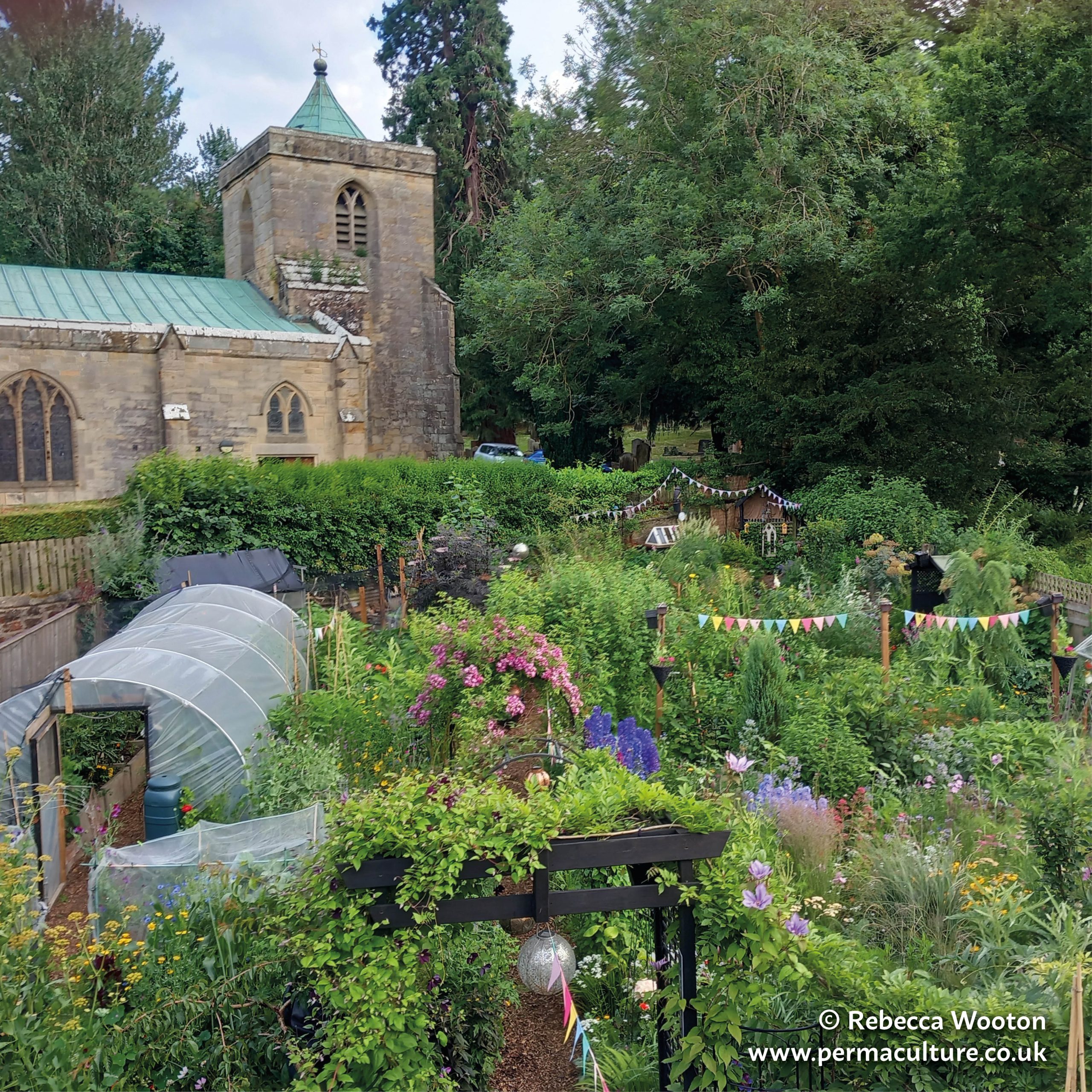

Animals can also perform tasks for us – they are natural forces we can work with. For example, we can use pigs to tractor land and prepare it for planting, sheep to crop grass (my local graveyard rarely sees a mower, the church uses sheep), chickens to weed and ducks to control pests.

When we learn about succession we start with weeds, rugged plants that colonise bare ground against the odds. In a society, we can also have ‘weeds’ – rugged individuals that colonise new ground – introducing entirely new ideas that the rest of society often finds preposterous. Bill Mollison is a classic weed, a man that swam against the tide of accepted ideas and predicted the effects of industrial monoculture on soil health and collapsing yields. Bill co-originated permaculture in Australia in the 1970s, way before most of us had woken up to the looming ecological crisis, as a response to his findings. Ghandi was a non-conformist weed. He refused to accept the British rule of India and implacably campaigned for independence. Nelson Mandela is also a weed, prepared to endure decades of prison and being accused of being a violent terrorist by supporters of apartheid.

Weeds in society are often implacable. They refuse to conform. They can consequently be very difficult characters! It is useful to remember that when you work with them and give them some leeway. We need weeds or our intellectual, artistic, scientific and philosophical ground would be bare of new ideas.

After the weeds come the pioneers, people who pick up the weed’s ideas and run with them. Whilst human weeds are like dock, couch grass, dandelions, nettle, all covering and stabilising the ground they inhabit, pioneers are the next level in our social ecosystem. Like broom, alder, gorse, they either bring in fertility or they set down their roots and start colonising another level. (Like pioneering bushes and small trees). These are the nitrogen fixers who fertilise the ground the weeds have colonised. They develop, evolve, test out, build ‘soil’, create new layers of understanding… They too can be implacable, apparently obsessed by exploring what is not commonly accepted wisdom. Pioneers are self-motivated, non-conformist, able to take concepts, ideas, discoveries and develop and adapt them. They can also be rather implacable and non-negotiable in relation to other people in their social group. If you identify a pioneer, you may excuse them for their forthright self-belief. They need it to carry the torch of the weed to the next step.

At the next stage of success we breathe a sigh of relief. Now is the time for the climax species to thrive. The bare soil has been colonised and fertility has been created. We have the roots, ground cover, bushes and small trees. The biodiversity of the habitat is beginning to thrive and the microclimate is created that can support the grand stability of the top canopy. Now is the time for the great oaks, the beeches, the giant redwoods, the tallest trees of the rainforest… the slower growing majestic entities of our forests and our oceans too. Here is the niche for the remarkable cetecea. In our culture, like our ecosystems, we can support and enjoy our climax species, those who take the work of the pioneers and weeds to another level. They are not to be confused with the barnstormers and non-conformists of the previous stages but they are able to synthesise the ideas and discoveries of their predecessors and develop them to another level of wisdom and insight. You could argue that Winston Churchill was a classic climax species, an example of a leader able to unite nations and inspire people to resist the evils of fascism.

There is another level of natural forces that we can explore, however, that is beyond the sphere of conventional science. This is one that has been understood in Chinese medicine for thousands of years, Ch’i. Ch’i is also known as the Lifeforce and is the energy of life. You are never more aware of the mysterious nature of Ch’i until we see a friend or relative’s newly deceased corpse. The person is there in body still but it is so obvious that we are seeing an empty shell and not the essence of the person we knew so well. It is a profound and humbling experience. The spark of life, so precious, has left.

That spark flows through us all. We can work with it or against it. How do we work with it? Good diet, exercise, mental attitude, balance, natural remedies that not only rebalance the physical body but also work with the person as a whole and help rebalance emotional and mental levels. We can also nourish the spirit by deepening our connection with this lifeforce by being out in nature, celebrating the changing seasons, the landscape, the changing weather patterns, the great open spaces… We all have individual ways of doing this. One of my favourite is to kayak in estuaries and in the sea, to swim in wild places, to climb hills. I want to revel in the beauty of the world and drink it in deep to nourish me when I have to go back to work at my desk.

The lifeforce can also be encouraged, cultivated and celebrated with other people, in our groups, in community, and ultimately in society. Great art and music has the capacity to do this as does the sharing of great science, philosophy, innovation and discovery. Where there is creativity of any kind within an ethical, life-enhancing framework that benefits humankind and our fellow species and ecosystems on this planet, we have the celebration of the lifeforce. This is why the ethics of Earth care, people care and fair shares are the basis of permaculture and why they matter so much. Society without ethics becomes dog eat dog, a resource grabbing race that ignores limits to growth, lacking compassion for less able or less advantaged people, and ultimately deeply destructive to the majority of people and the planet.

From this perspective, we return to the beginning of this series, my first article on the ethics of permaculture (see below).

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make and end is to make a beginning

The end is where we start from…

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Little Giddings, Four Quartets, T S Eliot

What is Permaculture: Part 1 – Ethics

7. Small Scale Intensive Systems – an original permaculture principle

Maddy Harland is the co-founder and editor of Permaculture magazine and author of Fertile Edges – Regenerating the land, culture and hope.