Permaculture traditionally advocates small-scale intensive systems. Instead of large-scale monocultures with huge fields that can handle machinery running on fossil fuels, used for fertilising, sowing and harvesting, on the farm we see a more traditional patchwork of small mixed polycultures that rely on biological resources, minimise or zero the use of fossil fuels, the use of some human labour and then techniques that mimic natural systems to produce yields and also reduce human labour. These include: Mulching to build fertility and reduce weeding; growing green manures, again to cover the ground and prevent weeds and to enhance fertility; the use of animals to ‘tractor’ ground instead of machines (pigs and chickens); mimicking the vertical layers of a stacked forest by planting roots, ground cover, small bushes, larger shrubs, small trees and then large trees in a progressive edge but substituting this natural pattern with edible, medicinal and useful species to create the highest possible yields.

This is for a number of reasons connected to their inherent sustainability. Small-scale systems are more productive per acre (in terms of yield of food per tonne) than monocultures. They are more biologically diverse and so are more ecologically stable. Large-scale monocultures require little human input but rely on fossil fuels to fertilise and transport their products, whilst small-scale systems require more human attention. Yet because of the way our food industry and economy is screwed, despite lower yields per acre, large scale monocultures make more money per acre in the global marketplace. They do not, however, sustain the land they use. Arguably they mine the soil of minerals and destroy it as a living food web. Neither are there the resources they require as inputs sustainable as these are finite – it is widely accepted in the scientific community that world oil reserves will not last forever and that techniques like fracking are energy intensive and polluting. In certain geological conditions fracking can also precipitate earthquakes.

Perhaps more sinister and more pressing is the issue of neonicotinoids – pesticides that act on insects’ central nervous systems and are increasingly blamed for problems with bee colonies. Despite new research pointing at their devastating effects the British Government has concluded that no change is needed in British regulation, against all advice from other EU countries.

The British position contrasts sharply with that of France, which in June [at the time of writing] banned one of the pesticides, thiamethoxam, made by the Swiss chemicals giant Syngenta. French scientists said it was impairing the abilities of honey-bees to find their way back to their nests. The Green MP Caroline Lucas described the British attitude as one of ‘astonishing complacency’.

Concern is growing around the world that the chemicals may affect the ability of bees to pollinate crops, something that would have catastrophic consequences for agriculture. Bee pollination has been valued at £200m per year in Britain and £128bn worldwide.

The French research was published in March in the journal Science at the same time as another study by British researchers from the University of Stirling, implicating neonicotinoids in the decline of bumblebees. The British team showed that production of queens, essential for bumblebee colonies to continue, declined by 85 per cent after they were exposed to ‘field-realistic levels’ of another neonicotinoid, imidacloprid, made by the German company Bayer.

One of the major problems with these form of pesticides is that they are ‘systemic’ – they are taken up into every part of the plant which is treated with them – including the pollen and nectar. This means that bees and other pollinating insects can absorb them and carry the poison back to their hives or nests. These chemicals do not discriminate and have a blanket effect on any pollinator, not just the insecticide’s target species.

Introduced by Bayer in the early 1990s, neonicotinoids have been an immense commercial success – Bayer’s imidacloprid was its top-selling insecticide in 2009, earning £510m – and have been used on vast areas. About 30 per cent of British cropland – 3.14 million acres – was being treated with the chemicals in 2010.

Clearly, this is a political and economic decision not a rational scientific decision. What would be the impact of losing bees from our ecosystems? Of about 240,000 flowering plants in North America, three quarters require the pollination of a bee, bird, bat or other animal or insect in order to bear fruit. It is now big business in countries like the USA and Australia to fly in and release bees to pollinate fields of crops from other countries.

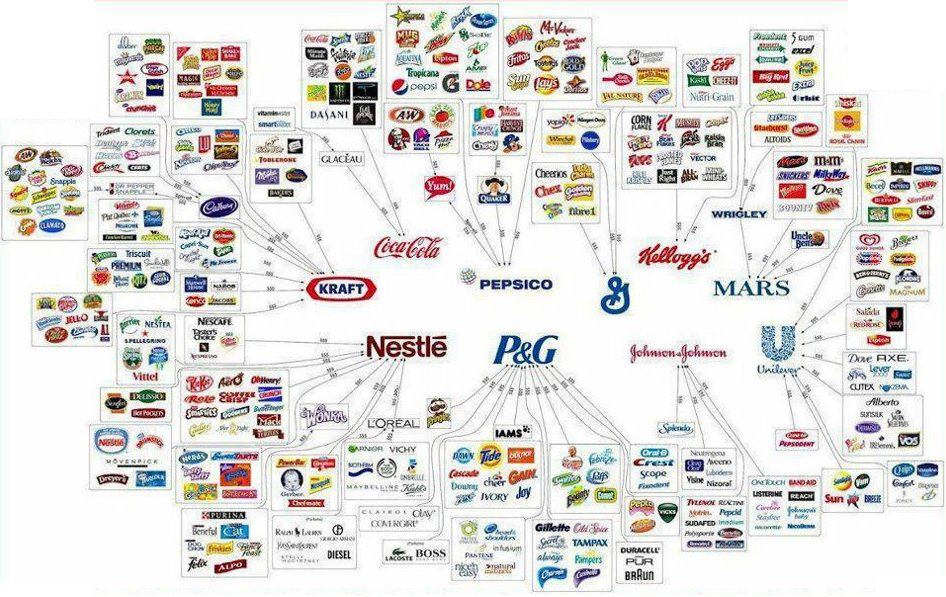

Our current global trend is all about economies of scale, sizing up, big being best and monopolies being most profitable. Corporates have manipualted our economic systems to facilitate this level of control. Our big global food industry is in reality controlled by 10 big companies: Coca-Cola, Associated British Foods (ABF), Danone, General Mills, Kellogg, Mars, Mondelez International (previously Kraft Foods), Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever. Together they earn around $1.1 billion in revenue per day in a $7 trillion food production industry that comprises about 10 percent of the global economy. It is clear by the plague of obesity, heart disease and Type 2 Diabetes in the industrialised world that their primary aim is profit, not the good health of consumers. (See Oxfam’s Behind the Brands Briefing Paper.)

I would argue that we should vote with our pockets, boycott these products and learn to cook inexpensive meals from raw ingredients either grown by ourselves or bought locally, preferrably from an organic producer whenever possible. If we choose to eat meat it should not be every day and should be farmed locally in small-scale systems or foraged. There is nothing quite so educational or humbling than the act of taking a life, whether it is livestock on a smallholding or farm or a wild creature, butchering it and eating it. Whatever your moral persuasion, there is no doubt, however, that commercially scaled meat products are carbon intensive. Finally, if we buy exotic products we should support artisanal producers. These choices would be a way of living this principle of small-scale intensive systems.

When we start looking at larger scales the critical factor is sustainability. This is where optimum sizing comes into play. We define ‘optimum’ as the most favourable or advantageous amount for a particular situation. So let’s start small and work up this idea.

* The optimum width for my rasied vegetable beds is twice the distance I can comfortably reach so that I can sow and weed and harvest in comfort. I am quite small in stature so my optimum sizing is going to be smaller than a tall man!

* There are optimum sizing for conserving rare breeds or endangered species to ensure that they are not made vulnerable by too much inter-breeding. We need to keep the gene pool healthy and as diverse as possible.

* There is also an optimum number of inhabitants for sustainable human settlements. At the Sustainability Centre, for example, there needs to be a certain number of resident staff and volunteers on the site to only perform tasks at different times of the day. For instance, we need to be here overnight to take care of guests staying in our eco-hostel or on our campsite. But optimum sizing for us is not all about function. We need a mixture of people on site with different skills and experiences and a balance of genders. Ideally, we need at least seven residents and the majority of them need to be permanent to meet our practical and the social needs. It is clear that solely employing 9-5 commuters and shift workers do not make this centre ‘sustainable’ or create community here.

* There are some optimium sizing for a publishing company. When Permanent Publications, who publish Permaculture magazine and a list of books, consisted of 3-4 people, it was really tough to get everything done. We just couldn’t efficiently edit, design, sell and physically post out a magazine issue yet alone produce books between each magazine without experiencing deep exhaustion. As soon as we could economically afford it, we started to build the team and also involve partners to share some of the tasks. Now we are a core group with eternal partnerships with other organisations that help us market and distribute our titles, things are much more manageable. In reality, however, we still need to grow to a team of seven to be at optimum size. As a group, we still do the work of more than one person. This means we do not have time to devote to other activities, like cultivating a really splendid permaculture garden (Tim and my ambition), for instance.

Should we, as permaculturists, always advocate small-scale intensive systems by default? With the majority of the world’s escalating population living in large cities this is an ideal that is not achievable. Permaculturists need to turn their attentions to designing large scale settlements and all the attendant elements that they require and trying to make them as sustainable as possible. To do this we need to embed other permaculture principles into our designs like energy cycling, for example, as our first strategy.

We also need to divide geographical areas of large cities into wards or zones. We can use political zoning but also zones can be defined by their function. A residential area is very different in character, resources and function to an industrial area. Ideally, we are looking at creating less defined functions and beginning the process of mixing functions or ideally becoming more multi-functional. We want residential buildings mixed with recreational areas, urban agriculture, community gardens, businesses, retail outlets, fabricators, manufacturers, artisans…

At the moment we divide everything up in our urban planning and dismantle community by zoning activities in a form of cultural monocultures. It leads to inner city shopping malls that are deserted at night, industrial estates with no green spaces, commuter ‘villages’ that are emptied of people in the daytime where no food is grown, power stations zoned outside of the city and no incentives to install micro-renewables and vast swathes of land devoted to industrial agriculture far away, where produce is shipped in by fossil fuel driven transport. Clearly, this left-brain zoning is neither energy efficient or culturally pleasant to live in.

Cuba is often idealised as a place that has developed urban abundance in the form of intensive inner city organic agriculture and rewenable energy in response to losing its supply of cheap oil when the Soviet Union collapsed and the USA embargo. Cuba has developed many examples of organic agriculture and export its skills and technqiues to other countries. It is not paradise but it has pioneered many examples that can be applied to cities seeking greater sustainability.

Another example is the city of Curitiba in Brazil where the problems of poverty, seasonal flooding, waste, transport and slums have been solved with little money but much political will and many ground-breaking ideas. Many of these are clear examples of applied permaculture principles. By defining the city’s problems, the people developed more manageable pathways to solving them. But the essence of this is the idea that optimum sizing is as much about physical sizing as it is about scaling and defining tasks on a mental level in order to make them achievable or solvable. We know this from our own experience. If we divide up tasks and schedule them, what can seem insurmountable can be achieved.

While permaculture systems are generally small-scale, this is not always the case. It is important that we do not limit our systems to being small-scale. Agroforestry systems can and are being designed and planted over large areas in the Amazon where original rainforest has been felled. This is a way of reintroducing biodiversity and establishing economic yeilds for local people, helping relieve the necessity of clear felling more rainforest.

Similarly, sustainable forestry is scaled up. Growing tree crops that will not be harvested at all to sink carbon or will be selectively harvested for high value timber is neither intensive or small-scale but it can incorporate permaculture design.

Another example is Sepp Holzer’s water retention landscapes. Sepp is not a small scale kind of guy and his vision for re-aquifying landscape is on a grand scale! We are talking entire watershed here, potentially strategies for water management in entire countries. See Desert of Paradise.

We must not regard permaculture design as a fixed discipline. How we understand how eco-systems work and apply and mimic those natural intelligence is an evolving processing. We still have so much to learn.

Maddy Harland is the co-founder and editor of Permaculture magazine and author of Fertile Edges – Regenerating the land, culture and hope.