Zones are rings of energy which usually spread out from the main centre of human activity on a site. Elements in a design are placed according to how often they are visited (and accessibility on the site). Areas that are visited most frequently, like an annual vegetable garden, greenhouse or a chicken run, are placed nearer the house. Orchards, grazing areas or a timber plantation, which need less attention, are placed further away.

The general principle of zoning on a large garden or farm are clearly described in Permaculture Design: Step by Step and The Earth Care Manual. Zones are not determined by tidy circles but by ease of access, paths, daily habits and preferences, microclimates, and other individual characteristics of the site.

Zoning in a small garden is no less important but is obviously less extensive. Though there may only be two zones, how elements are placed in the design for easy access and convenience is important. Home gardeners often juggle with outside commitments (work, family, community) which take them away from the garden, so gardening time has to be fitted in between other responsibilities. It is therefore important to place the propagation area, which needs daily attention, nearest the house, the annual vegetable garden and composting area close by for easy daily access and the hardier perennial plants/forest garden, however small, furthest away. These are also often more resistant to pest damage. Conventional garden design usually hides compost heaps and kitchen garden behind a hedge, away from the house. The permaculture kitchen garden has pride of place near the house and edible annuals, flowers, frog ponds, soft fruit and small fruit trees are mixed together in a healthy, diverse ecology.

Zones can be summarised thus:

Zone 0: the centre of human activity – house, barn (or village in a large design).

Zone 1: close to the house – kitchen garden, greenhouse, workshop, propagation frames, small animals like rabbits or guinea pigs, compost, wood store.

Zone 2: forest garden, chicken run, ponds, windbreaks, hedges.

Zone 3: beyond the scope of a small garden and containing unpruned, unmulched orchards, pasture, main crop, coppice and large trees for animal forage.

Zone 4: semi-managed, semi-wild area used for gathering, timber, wildlife and forest management.

The last zone, Zone 5, is an area of unmanaged land which is not designed. Here nature is allowed to take her course, volunteering flora and fauna without intervention from humans. Some permaculture designers advocate that we do not even enter this area and leave nature undisturbed. In countries where land is at a premium and gardens are small, it would be easy not to find a space for Zone 5, but is important to allow even a tiny area in a design to go wild. We all yearn for wilderness and it is in this zone that new volunteers often find an opening (such as wild flowers and grasses, insects, small mammals and birds).

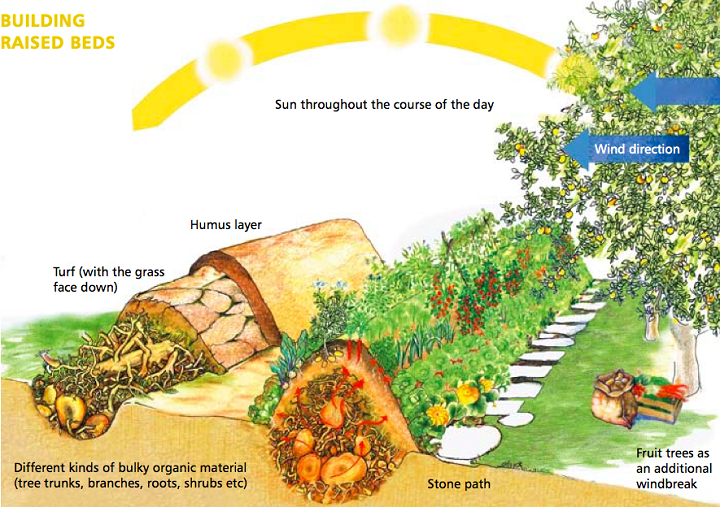

These are wild energies which come from outside the system and pass through it and include sun, light, wind, rain, water flow, wildfire. How we plant a garden is determined by the prevailing winds (placement of windbreaks and shelters), the angle at which the sun passes over the site (sun-loving plants and small fruiting bushes and trees to the sunny side, shade tolerant plants and larger trees furthest away from the path of the sun).

Slope takes account of the site in profile. It is best to place resources uphill and then use gravity to move them down. If possible, harvest water higher up than it is needed and use gravity to create a drip irrigation system. Plants which are drought tolerant and hardy do better higher up, plants which love water thrive lower down the slope. Nutrients, soil and other resources collect downhill.

3. Each Important Function Is Supported By Many Elements – An Original Permaculture Design Principle

Maddy Harland is the co-founder and editor of Permaculture magazine and author of Fertile Edges – Regenerating the land, culture and hope.