As days shorten and temperatures decline, sowing dates become more precise, because later sowings cannot regain lost time. It’s the opposite of spring when there are better growing conditions ahead, enabling later sowings to catch up. These sowing dates are based on a first frost and dark days by mid autumn; check local knowledge for your best timings.

Lettuce is still plentiful, from sowings in early summer, but leaves are more inclined to suffer mildew, and growth is reduced by aphid damage to roots. In contrast, endive is highly productive, and chards and basil continue. New flavours are chervil, salad rocket and leaves of oriental vegetables.

Around mid summer is the best time to sow chicories. The time at which you want harvests, and the warmth of your autumn, determine exact sowing dates. To harvest leaves in summer and autumn, we sow any time after the solstice, and for hearts in autumn we sow Palla Rossa types from solstice and through the following month. Hearts (radicchios) come ready at different times from the same sowing, and tend to rot after firming, so harvest their hearts as soon as they firm up.

There are varieties for long or round leaves, and with colours from white to yellow, pink and red. Another option is to harvest roots in late autumn to pot and then force in a dark place. Classically this is done with Witloof to produce yellow chicons in winter and spring, and with Treviso for pink chicons.

Autumn is a mirror image of spring in terms of growth patterns, except that the soil is warmer and harvests are bigger at first. Many plants have established root systems from earlier growth, so be prepared for some gluts in the first half of autumn.

Sow in late summer and enjoy your salads becoming more varied by the week. Coming into harvest season are rockets, orientals, endive, chicory, land cress, claytonia, lambs lettuce, spinach, chard, chervil and coriander. Lettuce has a secondary role by late autumn. Chervil The flavour of this herb brings appreciative comments from customers. Leaves are of similar shape to parsley but finer, more tender and with a taste of aniseed.

Sowing in summer is key, and Charles learnt the hard way in the 1980s, every year obeying seed packets’ instructions to sow chervil in spring. Each sowing produced few leaves before turning into a mass of little white flowers. Then an experimental summer sowing revealed the wonderful harvests of autumn, and beyond winter if it’s mild.

Salad rocket, Eruca sativa, grows differently to wild (wall-)rocket, Diplotaxis tenuifolia: both are of the brassicaceae family, but in different genera. Eruca rocket is annual, quick to make a flowering stem in spring and summer, while Diplotaxis is perennial.

The best period of cropping is autumn for Eruca, spring to early summer for Diplotaxis.

If you normally find rocket leaves too peppery, check out the milder leaves of young plants in autumn, from sowings 6-8 weeks earlier: rapid growth on a small root run gives mild-tasting leaves. Flavours strengthen as brassicas age, and cutting the small leaves of young plants is a way to have less pungency.

Mostly bred in Asia, these offer a pantheon of flavour, colour and form. The themes are fast growth, sappy and tender leaves, sometimes crunchy stems, with a wide spectrum of bright colours, and spicy, mustard flavours. Leaf radish is the fastest, a mooli with hairless leaves tasting of radish; the best variety is Sai Sai; Red Stemmed is pretty.

Mizuna (serrated) and mibuna (smooth edged) have long, thin leaves on long, pale stems; they are rapid growers, and there are red mizuna varieties too.

Mustards come in all shapes and colours: Red Frills (similar to Ruby Streaks) and Red Lace look wonderful in both garden and salads, milder flavoured than Green in the Snow’s taste of horseradish.

Pak choi and tatsoi are prolific in cooler conditions: their crunchy stems of small leaves add a bite to salads, with many types available.

Pest warning! These tender brassicas are loved by slugs, caterpillars and other pests. We find pak choi in particular is holed by slugs when nearby lettuce and spinach are slug free; possibly it needs a drier climate. Other autumn leaves Winter purslane, Claytonia perfoliata, offers succulent and mild-tasting leaves, at a time when most others are pungent or bitter. Plants respond well to cutting across the top. In spring the leaves themselves grow white flowers and look great in salads.

Land cress, Barbarea verna, is in the cabbage family, but like the rockets is in a different genus to most brassicas. Its leaves taste similar to watercress and plants can be cut over, or picked of outer leaves, a few at a time in mild winters.

Lambs lettuce (corn salad) is in season from mid autumn to early spring, see below.

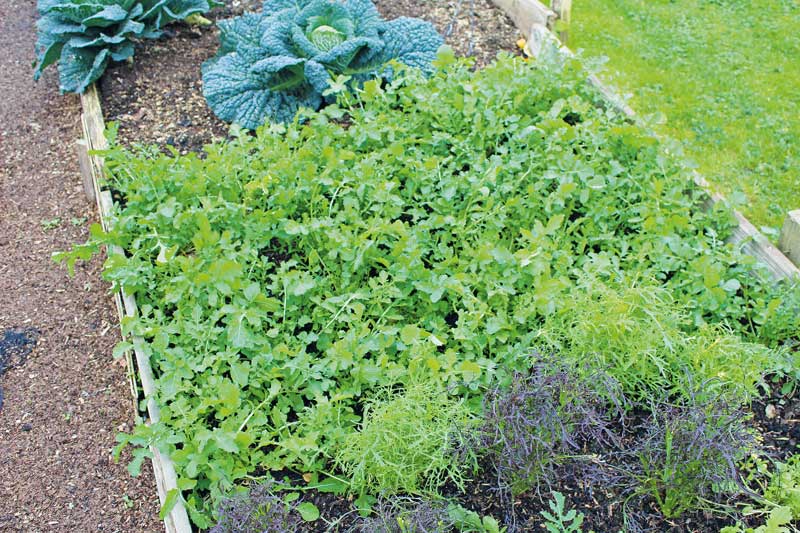

Salad rocket in late autumn, mustard Red Frills in front below

Late autumn, lambs lettuce was sown between fennel

Winter’s salad bowl has little leaves and big flavours. Leaves in high latitudes and continental climates are especially small and infrequent, even with protection. Lambs lettuce resists severe frost, land cress to a lesser extent.

There are none outdoors, with sowing for winter harvests completed in autumn. Outdoor lambs lettuce (corn salad, Valerianella locusta) The word ‘lettuce’ is a misnomer: at mature size after two to three months, plants are barely 10cm (4in) across and weigh less than 28g (1oz). Rather than growing larger, plants make side shoots, and the result is fiddly harvests in cold conditions. It’s fortunate that a buttery flavour and deep green colour recompense this.

Early growth is slow so a weed-free soil helps, or you can sow in modules to transplant. Lambs lettuce does not thrive in dry soil, because its mat of roots is at the surface, so water more regularly than other salads. Dry soil causes mildew on leaves, often a problem if it’s sown in summer.

Undercover allows a wide range of salad plants that grow slowly in cool conditions, and tolerate freezing. Some damage occurs below -8 to -10°C (18-14°F) and if these temperatures are common, lay fleece (row covers) over plants in a greenhouse or polytunnel, for extra insulation, as described in Eliot Coleman’s Winter Harvest Handbook.

Small, precious harvests in the depth of winter turn into regular feasts by late winter and early spring, off the same plants. One sowing in early autumn can give leaves until mid spring, so make notes to remind you of these sowing dates in autumn.†

Undercover spaces are often cropping tomatoes and other summer crops in early autumn, when these salads need sowing. Therefore sow in modules to have plants after four weeks, by which time the summer crops are finishing and can be removed.

They thrive in mild winters and resist frost, but are susceptible to slug damage. Tatsoi grows new leaves in even cooler conditions than pak choi, with a downside that it flowers earlier. The Savoy-leaved, larger varieties of tatsoi are easy to pick of their outer leaves, and a productive pak choi variety is Joi Choi F1.

Mustards for salad thrive in temperatures of 5-12°C (40-55°F), and in warmer weather their leaves often grow quickly to a size for cooking. In mild winters, you can pick regularly and for hot leaves, grow Green in the Snow.

Mustards flower in late spring, so an early autumn sowing gives leaves for five months off the same plants. In early spring the leaves are large and tender, before growing smaller as plants rise to flower. The yellow flowers and shoots are edible, with a spicy flavour.

Like the two rockets, true spinach, Spinacia oleracea, and leaf beet spinach, Beta vulgaris, share the same English name, but grow and taste differently. The Latin names inform us that leaf beet and chard are beetroots, while true spinach is in a different subfamily Chenopodiaceae, therefore related even to fat hen/lambs quarters, Chenopodium album.

For salads I recommend true spinach (Spinacia) which grows well in cool conditions, when the leaves also become sweet, even sugary; so although not abundant in midwinter, every leaf is a treat. In mild winters there can be a few outdoor spinach leaves, but they are often damaged by weather and for salad quality it’s best to give protection.

This article is extracted from No Dig Organic Home and Garden by Charles Dowding and Stephanie Hafferty. It’s available from PM’s online shop at https://shop.permaculture.co.uk

† See Charles Dowding’s Vegetable Garden Diary

No Dig Organic Home and Garden

by Stephanie Hafferty and Charles Dowding

Stephanie Hafferty is a no dig gardener, writer and author of The Creative Kitchen and coauthor of No Dig Organic Home and Garden.