There’s a plethora of info out there about comfrey but not much detail regarding establishing and managing a comfrey patch so I thought I would write an article to share my experience on this and how we grow comfrey as part of our fertility strategy in the market garden.

A member of the borage family, comfrey – Symphytum spp. is native to Europe and Asia and there are 40 recorded species throughout that region. The plant most commonly referred to and used in gardens is Russian comfrey – Symphytum x uplandicum, a naturally occurring hybrid of two wild species: common comfrey – Symphytum officinale and prickly comfrey – Symphytum asperum.

A few centuries back, the hybrid Symphytum x uplandicum came to the attention of Henry Doubleday (1810-1902) and he widely promoted the plant as a food and forage crop. Years later, and after two world wars, Lawrence D Hills (1911-1991) would continue Henry Doubleday’s Comfrey crusade.

In the 1950s, Hills developed a comfrey research program in the village of Bocking, near Braintree in the UK. The original trial site is on the plot of land now occupied by the Doubleday Gardens housing development. Lawrence Hills lived at 20 Convent Lane just around the corner of the trial site. At this site, Hills trialed at least 21 comfrey ‘strains’, each one named after the village Bocking. Strain 14 was identified as being the most nutrient rich, non-seeding strain and ‘Bocking 14’ began its journey into gardens far and wide across the world. (Learn more its history on the Balkan Ecology Project blog.)

Medicinal – Comfrey has been cultivated as a healing herb since at least 400BC. The Greeks and Romans commonly used comfrey to stop heavy bleeding, treat bronchial problems and heal wounds and broken bones.

Poultices were made for external wounds and tea was consumed for internal ailments. Comfrey has been reported to promote healthy skin with its mucilage content that moisturizes and soothes and promotes cell proliferation.

This plant is my first port of call if ever I need to dress a wound. Simply take a few leaves brush them together to remove the hairs and wrap them around the wound and apply light pressure. It’s incredibly effective at stopping the bleeding, reducing the pain and healing the wound.

Biomas – Comfrey produces large amounts of foliage from late May (late spring) until hard frosts in October or November (late autumn). The plant is excellent for producing mulch and can be cut from 2-5 times per year depending on how well the plants are watered and fed. The plant grows rapidly after each harvest.

In our gardens we have Comfrey ‘Bocking 14’ located next to each fruit tree in order to have a renewable source of mulch just where we need it. We also grow in patches as part of our fertility strategy in the market garden and have patches in the wildflower meadows (details below).

We’ve supplied 1,000 ‘Bocking 14’ cuttings to Oxygenisis, a business in Germany who are experimenting with using this plant for carbon capture.

Mineral dam – Comfrey has deep roots of up to 2m that utilize nutrients deep in the subsoil that would otherwise wash away with the underground soil water or remain inaccessible to other plants. The nutrients, once taken up from the roots, are relocated throughout the plant as and where needed with some of them ending up in the comfrey leaf mass. When cutting the leaf mass and applying to the soil surface, the mined nutrients are returned and again made accessible to shallower rooted crop plants.

Biodiversity – The bell shaped flowers provide nectar and pollen to many species of bees and other insects from late May until the first frosts in late autumn. Lacewings are said to lay eggs on comfrey and spiders overwinter on the plant. Parasitoid wasps and spiders will hunt on and around comfrey.

Pest and disease prevention and control – Research indicates that a comfrey solution can be used to prevent powdery mildew. Pest predators such as spiders, lacewings and parasatoid wasps associate with this plant. It’s best to leave some plants alone in order to sustain pest predator relationships.

Ground cover – Some species can quickly spread to form a thick ground cover and work particularly well for ground cover on the sunny side under shrubs and trees. Symphytum tuberosum – Tuberous Comfrey seems to be the best species for this.

Fertilizer – Comfrey leaves contain a great balance of major plant nutrients (N,P,K) and can be fed to plants as powder, direct mulch or by steeping chopped comfrey leaves in water for several weeks to produce a thick, dark liquid that can be diluted with water and applied to plant roots. More on this below.

Nutritional value of comfrey – You can see from the below table that wilted comfrey contains significantly higher quantities of potash compared to other organic fertilizers. It’s well recorded that comfrey is an excellent source of potassium (K) a major plant nutrient that is required by plants in large amounts for proper growth and reproduction.

Animal fodder – Comfrey has a long history for use as an animal feed. Lawrence D Hills dedicated books to this topic.* The leaves are best received by animals wilted. Fresh leaves can be eaten by pigs, sheep, and poultry but cattle, rabbits and horses will only consume wilted leaves.

Human consumption – Symphytum officianale and Symphytum x uplandicum are both reported to be used for salad and potherb and are best when cooked. Personally I’m not keen on the texture but will have the occasional nibble from the garden using the new growth to mix in a spring green salad.

Caution – Although comfrey has been used as a food crop, in the past 20 years scientific studies reported that comfrey may be carcinogenic, since it appeared to cause liver damage and cancerous tumors in rats. These reports have temporarily restricted development of comfrey as a food crop. In light of this, the regular consumption of comfrey is not advisable.

Life cycle – Herbaceous perennial

Growth habit – Comfrey begins growth in early-April and by early May compact clusters of young leaves are visible in the crown of the old plant. Within a few weeks, the leaf blades with long petioles have grown to over 35cm high. Basal leaves are large, lance-shaped, stalked, and coarsely hairy. The leaves die back following the first frost and remain dormant for winter. Many species can spread vigorously via seed and are generally not welcome in the garden because of this. Other species can spread via tubers and all species quickly regenerate from broken root pieces.

Flowering – Starts in late May or early June and continues until the first frost in late autumn. The bell-shaped flowers with pedicels are in terminal cymes or one-sided clusters. Flowers of common comfrey are usually creamy yellow, but white, red, or purple types have been found in Europe. Prickly comfrey has pink and blue flowers while Russian comfrey has blue, purple, or red-purple flowers. Tuberous comfrey has creamy white flowers. Vegetative growth does not cease with the start of flowering, and the plant will add new stems continuously during the growing season. Most comfrey plants can be somewhat invasive, spreading via seed to parts of the garden where they are not wanted. ‘Bocking 14’ will flower and provide nectar and pollen but will not produce viable seed.

Roots – Some species have short, thick, tuberous roots such as Symphytum tuberosum. Others such as Symphytum x uplandicum have deep and expansive root systems.

Light – Needs full sun for good biomass production but grows fine in the shade.

Shade – Tolerates light shade (about 50%).

Moisture – Some species are drought tolerant e.g. Symphytum tuberosum. Cultivated plants require irrigation.

USDA Hardiness Zone – 4-9 comfrey crowns and roots are very winter hardy.

Soil – Comfrey is adaptable to many soils, but prefers moist, fertile soils.

pH – Tolerates a wide range (6.5-8.5), although not very sensitive to soil pH, highest yields are reported to occur on soils with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0.

Perhaps you’re interested in growing comfrey to feed your animals, for medicine, for mulch, for compost or you’re slightly masochistic and want to roll around naked in the pricky beds of biomass (not me). In any case, here’s how to do it.

The plant we use in our gardens is Symphytum x uplandicum – ‘Bocking 14’. A sterile cultivar that produces copious quantities of nutrient dense biomass. The following information is based on using this plant.

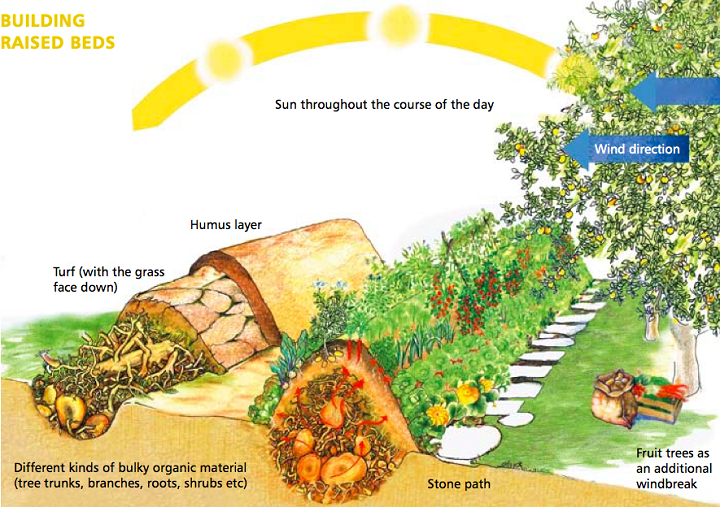

Choosing the site – We’re growing for biomass and want the plants to receive as much light as possible. Accordingly, we lay out our beds on an east to west axis (we’re in the northern hemisphere).

Irrigation is necessary if you want to get good yields from the plants so picking a place with access to irrigation is of paramount important.

In areas of low rainfall, using the gradient of the land to channel precipitation towards your beds will reduce the water needs of your plants. In areas of high rainfall with a high water table you should consider diverting water away from the beds.

Once established, comfrey is difficult to get rid of, so choose a site where you want it to stay. Don’t plant comfrey in any area you cultivate, as the broken root pieces quickly establish into new plants and can out compete slower growing crops.

Position comfrey downhill from where you expect leachate to be present, i.e downhill from a manure pile , compost heap, outside toilet, animal pen etc., can provide passive fertility to the plants and rescue otherwise lost minerals from draining away with the sub soil ground water.

Grow the comfrey where you want to use it. As you’ll see later we may be harvesting over 1/4 ton biomass from our patch and don’t want to be carrying that over long distances.

Preparing the site – Raised beds are a major part of our fertility strategy and overtime retain water and nutrients very efficiently. I use 1.3m wide beds surrounded by 50cm paths for our crops as this allows easy access for harvesting everywhere in the beds without ever having to tread on the soil and the paths are wise enough to take our lawnmower.

To form a bed, the area should be cleared of all plants, which is best achieved by sheet mulching the season before. Pernicious perennials or tap rooted biennials should be dug out. After you have cleared the whole area, mark out the bed shape with string and dig out 50cm wide paths around your beds, applying the soil to the surface of the planting area and thereby creating the initial rise of the bed. Fork over the beds well. If a hardpan is present take the time and effort to eliminate it before planting.

Depending on the quality of your soil you may want to add extra compost before planting into the bed. If you have sheet mulched the area before hand, with the additional soil from the paths all you need to do is add a good 20cm thick straw mulch (or some other mulch) and it’s ready for planting. A good mulch to start with will help keep the weeds down while your comfrey gets going.

You can alter the depth and gradient of the paths to facilitate the required direction of water movement.

Planting material – You can plant out with crown divisions or root cuttings best done in the spring when the soil has warmed. A crown division can be obtained from simply putting a spade through the center of a mature comfrey plant and transplanting the divided sections. For our beds, I divided two year old plants into quarters, sometimes sixths, and these established very well in the first year. It’s bests not to harvest the leaf biomass in the first year in order to allow a deep root system to develop. However if you use large divisions you can start harvesting in July.

Root cuttings are a great way to plant out large areas of comfrey. The cuttings should be grown on in small pots with 50% compost 50% river sand mix kept moist and planted out in the spring as soon as the first leaves emerge and the soil has warmed. If you are planting large numbers of root cuttings you can plant directly into the beds by creating ‘nests’ in the straw, adding two cupped handfuls of the above mentioned potting mix and plant the cuttings into this. Keep them moist like a wrung out sponge and the success rate will be very close to 100%.

Spacing – The plants should be spaced 60cm apart in rows and 60cm apart at diagonals between rows. Plant the rows 15cm from the edge of the beds.

Cutting – In the first year allow the plants to establish so that the roots develop well and penetrate deep into the subsoil. Remove any weeds around the plants leaving them on the surface. The following year the cutting can begin. You can scythe the beds for a quick harvest or cut each plant individually with a pair of secateurs or shears cutting to 5cm or so from ground level.

The leaves are prickly so if you have sensitive hands wear gloves. Cut the comfrey as the flowering stalks emerge up to four times a year. Allow the plants to flower at least once during the season to provide bee fodder to a range of native bees and honey bees. Leave the last flush of leaves before the winter so that invertebrates can find winter shelter in the undergrowth. You may need to weed between cuts every now and then but generally the comfrey will quickly cover the surface.

Feeding – After you have cut the comfrey, mow the pathways between the beds and empty the trimmings to the base of the comfrey plants. Any trimmings from lawns and hedges in the surrounding area can also be used.

We are experimenting with growing nitrogen fixing hedging and ground cover plants adjacent to the patch in order to feed our comfrey.

A most excellent comfrey feed is undiluted urine applied at a rate of approx 500 ml per plant twice per growing season.

Irrigation – Comfrey will produce more biomass if irrigated and in dry climates it’s essential to irrigate. Comfrey plants wilt very fast in hot conditions and will stop photosynthesising at this point. Twenty litres per m2 per week of drought should be more than adequate. The beauty of biological systems are that, if managed properly, each year the soils improve and the ability of the soil to store water will improve over time.

We use passive irrigation diverting water from a mountain stream into the paths around the beds. The paths fill with water, we raise the level by blocking the low points with sacks of sawdust and the water is drawn throughout the soil via capillary action.

Passive irrigation in our market garden. The paths fill with water and the water permeates throughout the soil via capillary action.

As mulch – Freshly cut comfrey leaves make good mulch because they have high nitrogen content, and don’t pull nitrogen from the soil while decomposing. Comfrey’s high potassium content makes it especially beneficial for vegetables such as tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers, berries, and fruit trees.

With adequate feed and watering we’ve seen yields of 2-3kg of biomass per plant per cut.

Comfrey beds establishing well. This bed was planted with divided crowns 5 months prior to this photo being taken.

Liquid fertliser – What I like to call ‘Comfert’. Fill a barrel, preferably with a bottom tap and a gauze on the inside (to prevent clogging) about 3/4 full with freshly cut comfrey and add water to fill the barrel. Cover it, and let it steep for 3-6 weeks. The smell from the resulting liquid is far from attractive so approach with caution. The tea may be used full strength or diluted by half or more. Don’t apply before heavy rain is forecast as most of the nutrients suspended in the liquid will wash straight through the soil. For the best results apply the feed to your vegetables when they are in most need of the extra fertility. This will be different for each crop, for example, tomatoes are best fed when they are setting fruit and then any time during the fruiting period. Applying comfert before this can be counter productive and make your plants more susceptible to pest problems. The black slurry at the bottom of the barrel can be dispersed evenly back over the comfrey patch.

Liquid fertilizer concentrate – ‘Comfert Plus’ can also be made by packing fresh-cut comfrey tops into an old bucket, weighing them down with something heavy, covering tightly, and waiting a few weeks for them to decompose into a black slurry. You can put a hole in the bottom of the bucket and collect the concentrate in another container as it drips out. Dilute this comfrey concentrate about 15 to 1 with water, and use as you would comfert. You can seal this concentrate in plastic jugs until you are ready to use it.

Warning! Comfert stinks like hell. My nieces came to visit from London last year and offered to help out in the market garden. One of the tasks that day was to apply comfert to the crops. Let’s just say it did not end well and we had a much better experience taking softwood cuttings the next day.

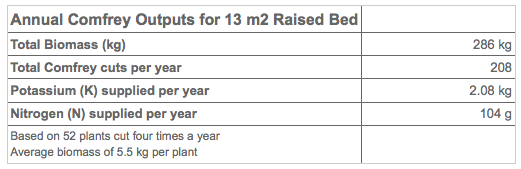

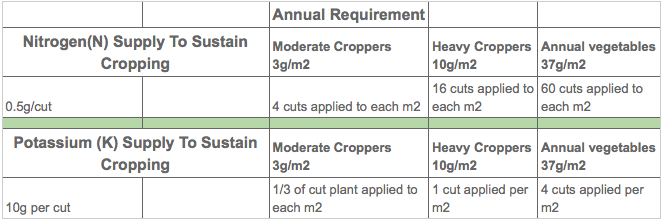

According to Martin Crawford in Creating a Forest Garden: Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops, one cut of comfrey from one plant contains 0.5g of Nitrogen (N) and 10g of potassium (K) to crops.

Based on this I calculated how much Potassium (K), Nitrogen (N) and biomass the 13 m2 comfrey patch can potentially produce in a year.

Below is a table indicating how many comfrey cuts are needed to meet the Nitrogen and Potassium needs of various moderate and heavy cropping fruit and nut trees and annual vegetables.

In the 1960s, Lawrence D. Hills used UK gardeners records for a comfrey report. (See the Balkan Ecology Project blog for the results.)

Based on these records I calculated a yield of approx. 5.5kg of biomass per plant each year. Using this figure one of our beds should produce approx 286kg of biomass. We shall see as this year we begin our own records. We’re looking to gather some solid data on how comfrey performs in our climate and we’ll be recording the yields from our patch starting this season and for at least the next five years. For more info on our record keeping and research programs see Polyculture Market Garden Study.

If you would like to join the ‘who can grow the most comfrey’ experiment and contribute data to our records, send us an email. It will be great to have records from all over the world.

For the full article from the Balkan Ecology Project visit HERE

Book: No Dig Organic Home and Garden

Watch: The many uses of comfrey

Paul runs the Balkan Ecology Project in Bulgaria with his wife Sophie Roberts and their two boys Dylan and Archie.